!pip install pywaffle

!pip install spacy

!pip install plotnine

!pip install great_tables

!pip install wordcloud1 Introduction

1.1 Recap

As mentioned in the introduction to this section on natural language processing, the main goal of the techniques we will explore is the synthetic representation of language.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) aims to extract information from text through statistical content analysis. This definition includes a wide range of NLP applications (translation, sentiment analysis, recommendation, monitoring, etc.).

This approach involves transforming a text—understandable by humans—into a number, which is the appropriate format for a computer in the context of statistical or algorithmic approaches.

Turning textual information into numerical values suitable for statistical analysis is no easy task. Text data are unstructured since the sought-after information—specific to each analysis—is hidden in a large mass of information that must also be interpreted within a certain context (the same word or phrase can have different meanings depending on the context).

If that wasn’t already difficult enough, there are additional challenges specific to text analysis, as this data is:

- noisy: spelling, typos…

- evolving: language changes with new words, meanings…

- complex: variable structures, agreements…

- ambiguous: synonymy, polysemy, hidden meanings…

- language-specific: no single set of rules applies across languages

- high-dimensional: infinite combinations of word sequences

1.2 Chapter Objective

In this chapter, we will focus on frequency-based methods within the bag of words paradigm. These are somewhat old school compared to the more sophisticated approaches we’ll cover later. However, introducing them allows us to address several typical challenges of text data that remain central in modern NLP.

The main takeaway from this section is that since text data is very high-dimensional—language is a rich object—we need methods to reduce the noise in our text corpora to better capture the signal.

This part serves as an introduction, drawing on classic works of French and English literature. It will also present some key libraries that form part of the essential toolkit for data scientists: NLTK and SpaCy. The following chapters will then focus on language modeling.

NLTK is the historical text analysis library in Python, dating back to the 1990s. The industrial application of NLP in the world of

data science is more recent and owes a lot to the increased collection

of unstructured data by social networks. This has led to a renewal of the NLP field, both in research and in its industrial application.

The spaCy package is one of the tools that enabled

this industrialization of NLP methods. Designed around the concept of data pipelines, it is much more convenient to use

for a text data processing chain that involves

multiple transformation steps.

1.3 Method

Text analysis aims to transform text into manipulable numerical data. To do this, it is necessary to define a minimal semantic unit. This textual unit can be a word, a sequence of n words (an ngram), or even a string of characters (e.g., punctuation can be meaningful). This is called a token.

Various techniques (such as clustering or supervised classification) can then be used depending on the objective, in order to exploit the transformed information. However, text cleaning steps are essential. Otherwise, an algorithm will be unable to detect meaningful information in the infinite range of possibilities.

The following packages will be useful throughout this chapter:

2 Example Dataset

2.1 The Count of Monte Cristo

The example dataset is The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas. It is available for free on the http://www.gutenberg.org (Project Gutenberg) website, along with thousands of other public domain books.

The simplest way to retrieve it

is to use the request package to download the text file and slightly

clean it to retain only the core content of the book:

import requests

import re

url = "https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17989/17989-0.txt"

response = requests.get(url)

response.encoding = 'utf-8' # Assure le bon décodage

raw = response.text

dumas = (

raw

.split("*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 17989 ***")[1]

.split("*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 17989 ***")[0]

1)

def clean_text(text):

text = text.lower() # mettre les mots en minuscule

text = " ".join(text.split())

return text

dumas = clean_text(dumas)

dumas[10000:10500]- 1

- On extrait de manière un petit peu simpliste le contenu de l’ouvrage

" mes yeux. --vous avez donc vu l'empereur aussi? --il est entré chez le maréchal pendant que j'y étais. --et vous lui avez parlé? --c'est-à-dire que c'est lui qui m'a parlé, monsieur, dit dantès en souriant. --et que vous a-t-il dit? --il m'a fait des questions sur le bâtiment, sur l'époque de son départ pour marseille, sur la route qu'il avait suivie et sur la cargaison qu'il portait. je crois que s'il eût été vide, et que j'en eusse été le maître, son intention eût été de l'acheter; mais je lu"2.2 The Anglo-Saxon Corpus

We will use an Anglo-Saxon corpus featuring three authors of gothic literature:

- Edgar Allan Poe, (EAP);

- HP Lovecraft, (HPL);

- Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, (MWS).

The data is available in a CSV file provided on GitHub. The direct URL for retrieval is

https://github.com/GU4243-ADS/spring2018-project1-ginnyqg/raw/master/data/spooky.csv.

Having a corpus that compares multiple authors will allow us to understand how text data cleaning facilitates comparative analysis.

We can use the following code to read and prepare this data:

import pandas as pd

url='https://github.com/GU4243-ADS/spring2018-project1-ginnyqg/raw/master/data/spooky.csv'

#1. Import des données

horror = pd.read_csv(url,encoding='latin-1')

#2. Majuscules aux noms des colonnes

horror.columns = horror.columns.str.capitalize()

#3. Retirer le prefixe id

horror['ID'] = horror['Id'].str.replace("id","")

horror = horror.set_index('Id')The dataset thus pairs an author with a sentence they wrote:

horror.head()| Text | Author | ID | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Id | |||

| id26305 | This process, however, afforded me no means of... | EAP | 26305 |

| id17569 | It never once occurred to me that the fumbling... | HPL | 17569 |

| id11008 | In his left hand was a gold snuff box, from wh... | EAP | 11008 |

| id27763 | How lovely is spring As we looked from Windsor... | MWS | 27763 |

| id12958 | Finding nothing else, not even gold, the Super... | HPL | 12958 |

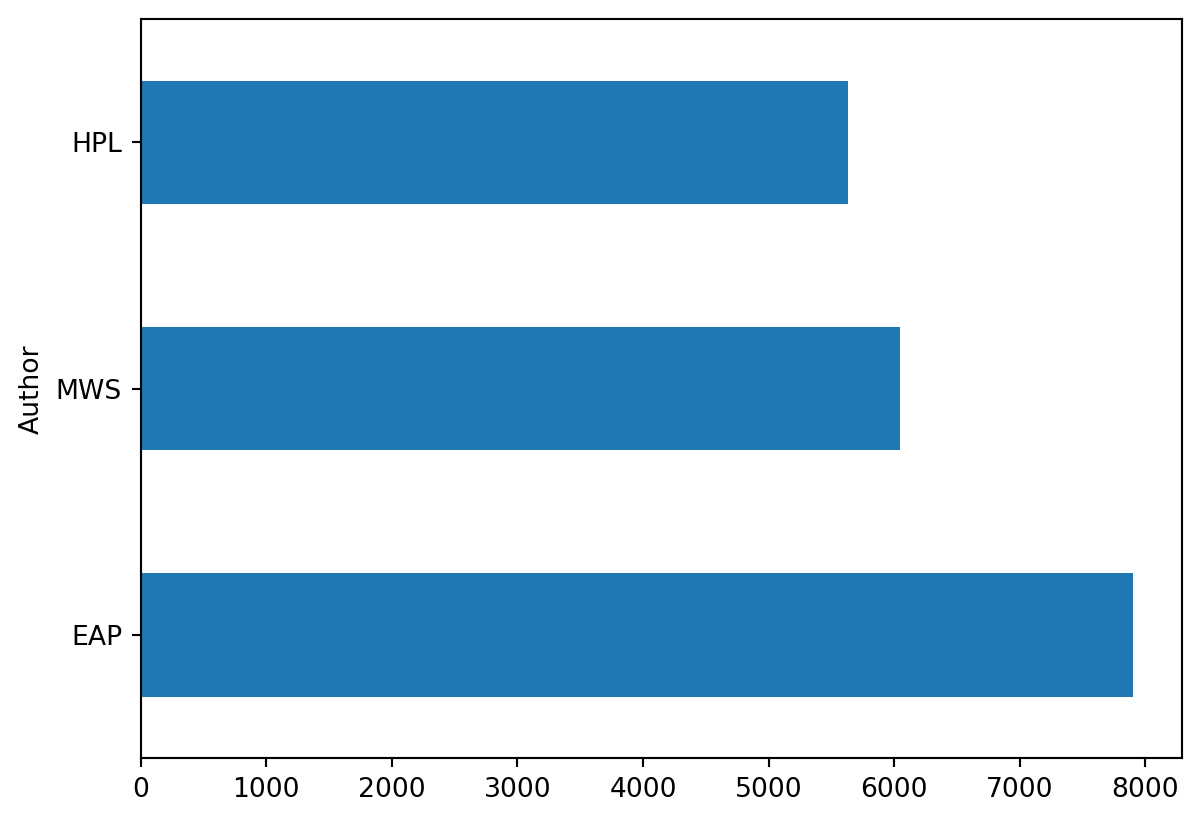

We can observe that the excerpts from the 3 authors are not necessarily balanced within the dataset. If this corpus is later used for modeling, it will be important to account for this imbalance.

3 Initial Frequency Analysis

The standard approach in statistics—starting with descriptive analysis before modeling—also applies to text data analysis. Text mining therefore begins with a statistical analysis to determine the structure of the corpus.

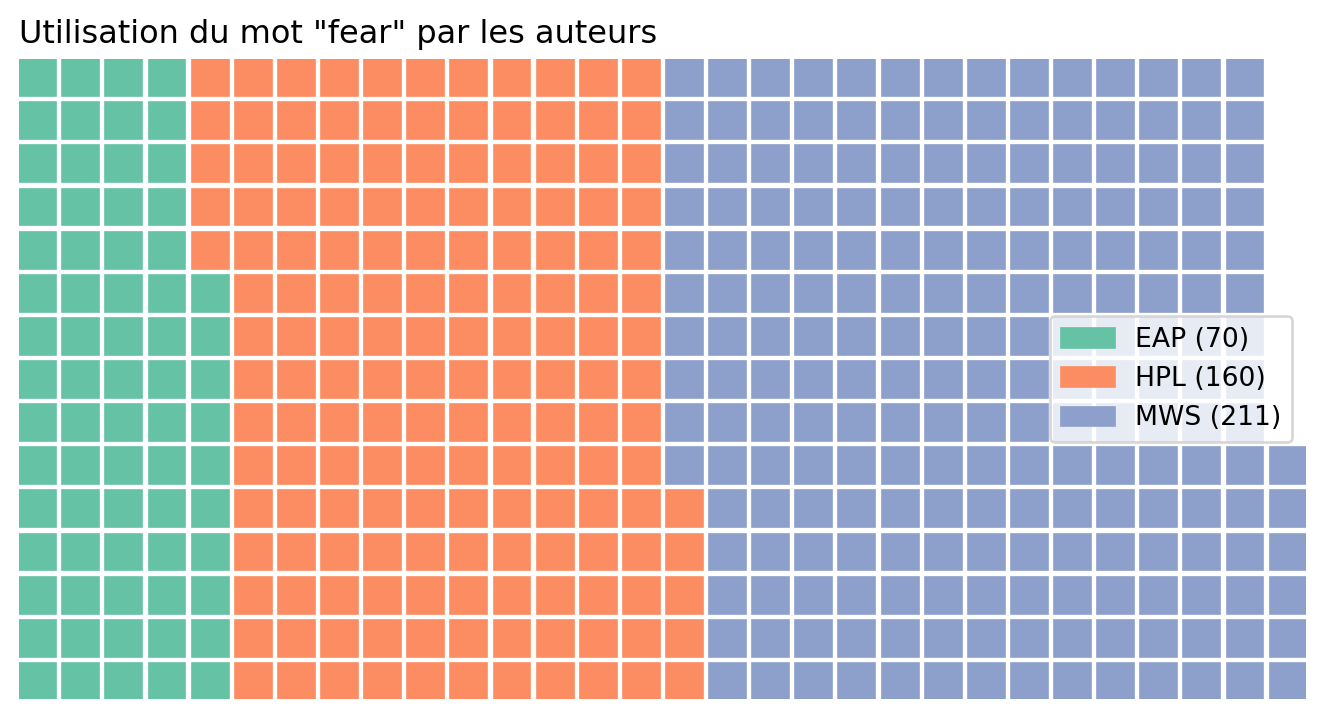

Before diving into a systematic analysis of each author’s lexical field, we will first focus on a single word: fear.

3.1 Targeted Exploration

The exercise below presents a graphical representation called a waffle chart. This is a better alternative to pie charts, which are misleading because the human eye can be easily deceived by their shape, which does not accurately represent proportions.

First, we will focus on our Anglo-Saxon corpus (horror)

- Count the number of sentences, for each author, in which the word

fearappears. - Use

pywaffleto generate the charts below that visually summarize the number of occurrences of the word “fear” by author. - Repeat the analysis with the word “horror”.

The resulting count should be as follows

| wordtoplot | |

|---|---|

| Author | |

| EAP | 70 |

| HPL | 160 |

| MWS | 211 |

This produces the following waffle chart:

This clearly highlights the imbalance in our dataset when focusing on the term “fear”, with Mary Shelley accounting for nearly 50% of the observations.

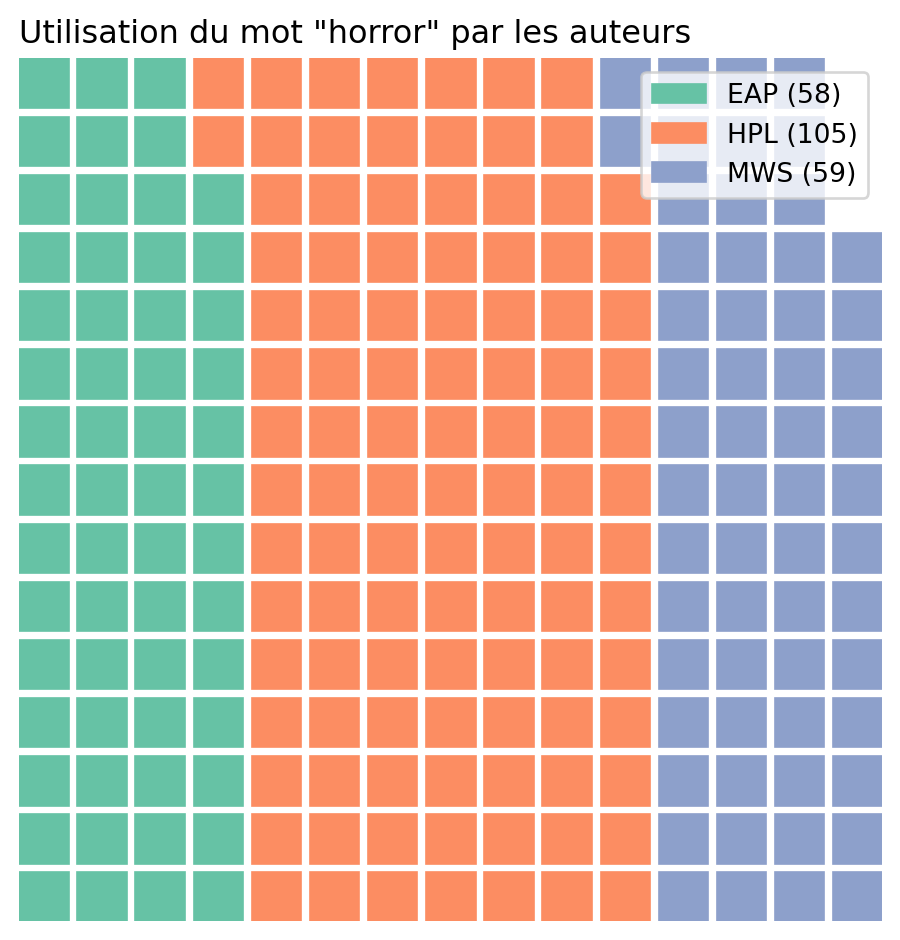

If we repeat the analysis with the term “horror”, we get the following figure:

3.2 Converting Text into Tokens

In the previous exercise, we performed a one-off search, which doesn’t scale well. To generalize this approach, a corpus is typically broken down into independent semantic units: tokens.

We will need to import several ready-to-use corpora to work with the NLTK or SpaCy libraries. The instructions below will help you retrieve all these resources.

To retrieve all our ready-to-use NLTK corpora, we do the following

import nltk

nltk.download('stopwords')

nltk.download('punkt')

nltk.download('punkt_tab')

nltk.download('genesis')

nltk.download('wordnet')

nltk.download('omw-1.4')For SpaCy, it is necessary to use

the following command line:

!python -m spacy download fr_core_news_sm

!python -m spacy download en_core_web_smRather than implementing an inefficient tokenizer yourself, it is more appropriate to use one from a specialized library. Historically, the simplest choice was to use the tokenizer from NLTK, the classic Python text mining library:

from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

word_tokenize(dumas[10000:10500])As we can see, this library lacks detail and has some inconsistencies: j'y étais is split into 4 tokens (['j', "'", 'y', 'étais']) whereas l'acheter remains a single token. NLTK is an English-centric library, and its tokenization algorithm is not always well-suited to French grammar rules. In such cases, it is better to use SpaCy, the more modern library for this kind of task. Besides being well-documented, it is better adapted to non-English languages. As shown in the documentation example on tokenizers, its algorithm provides a certain level of sophistication:

It can be applied in the following way:

import spacy

from spacy.tokenizer import Tokenizer

nlp = spacy.load("fr_core_news_sm")

doc = nlp(dumas[10000:10500])

text_tokenized = []

for token in doc:

text_tokenized += [token.text]

", ".join(text_tokenized)" , mes, yeux, ., --vous, avez, donc, vu, l', empereur, aussi, ?, --il, est, entré, chez, le, maréchal, pendant, que, j', y, étais, ., --et, vous, lui, avez, parlé, ?, --c', est, -, à, -, dire, que, c', est, lui, qui, m', a, parlé, ,, monsieur, ,, dit, dantès, en, souriant, ., --et, que, vous, a, -t, -il, dit, ?, --il, m', a, fait, des, questions, sur, le, bâtiment, ,, sur, l', époque, de, son, départ, pour, marseille, ,, sur, la, route, qu', il, avait, suivie, et, sur, la, cargaison, qu', il, portait, ., je, crois, que, s', il, eût, été, vide, ,, et, que, j', en, eusse, été, le, maître, ,, son, intention, eût, été, de, l', acheter, ;, mais, je, lu"As we can see, there are still many elements cluttering our corpus structure, starting with punctuation. However, we will be able to easily remove these later on, as we will see.

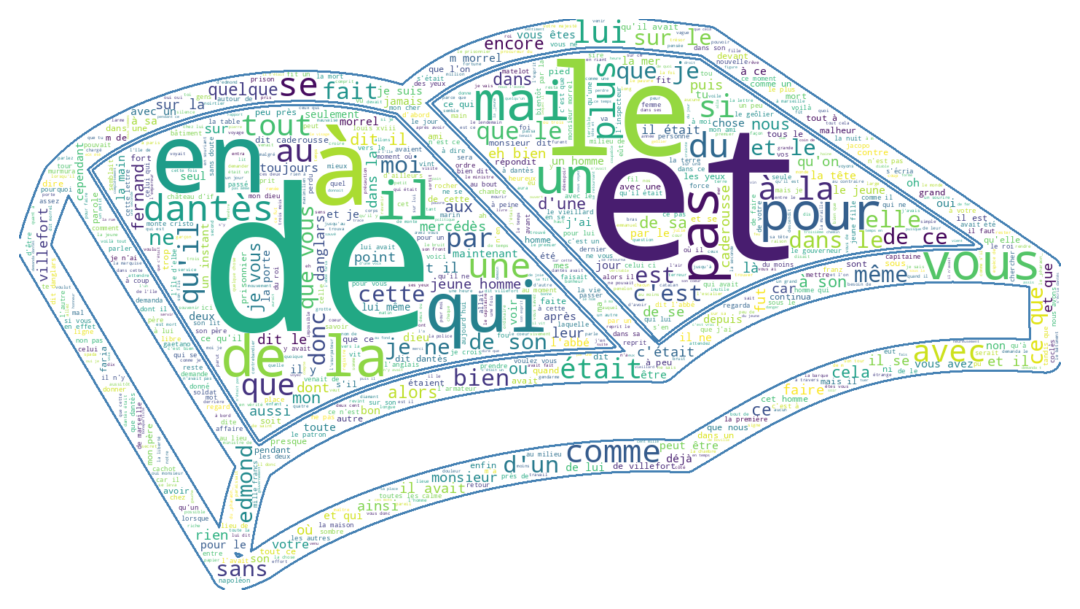

3.3 Word Cloud: A First Generalized Analysis

At this point, we still have no clear sense of the structure of our corpus: word count, most frequent words, etc.

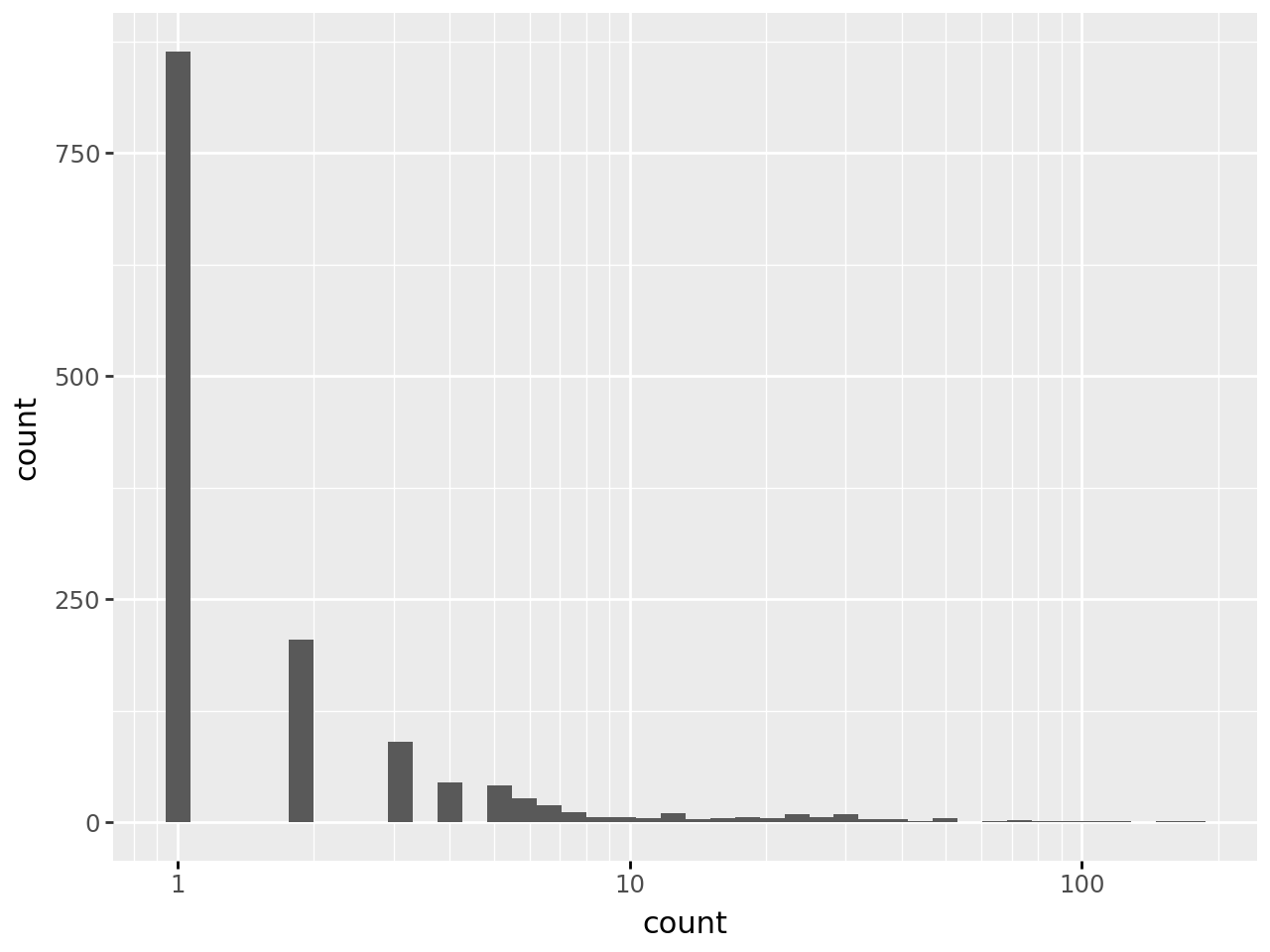

To get an idea of the corpus structure, we can start by counting word distribution in Dumas’ work. Let’s begin with the first 30,000 words and count the unique words:

from collections import Counter

doc = nlp(dumas[:30000])

# Extract tokens, convert to lowercase and filter out punctuation and spaces

tokens = [token.text.lower() for token in doc if not token.is_punct and not token.is_space]

# Count the frequency of each token

token_counts = Counter(tokens)There are already many different words in the beginning of the work.

len(token_counts)1401We can observe the high dimensionality of the corpus, with nearly 1,500 unique words in the first 30,000 words of Dumas’ work.

token_count_all = list(token_counts.items())

# Create a DataFrame from the list of tuples

token_count_all = pd.DataFrame(token_count_all, columns=['word', 'count'])If we look at the distribution of word frequencies—an analysis we will extend later when discussing Zipf’s law—we can see that many words are unique (nearly half), that the frequency density drops off quickly, and that we should focus more on the tail of the distribution than the following figure allows:

from plotnine import *

(

ggplot(token_count_all) +

geom_histogram(aes(x = "count")) +

scale_x_log10()

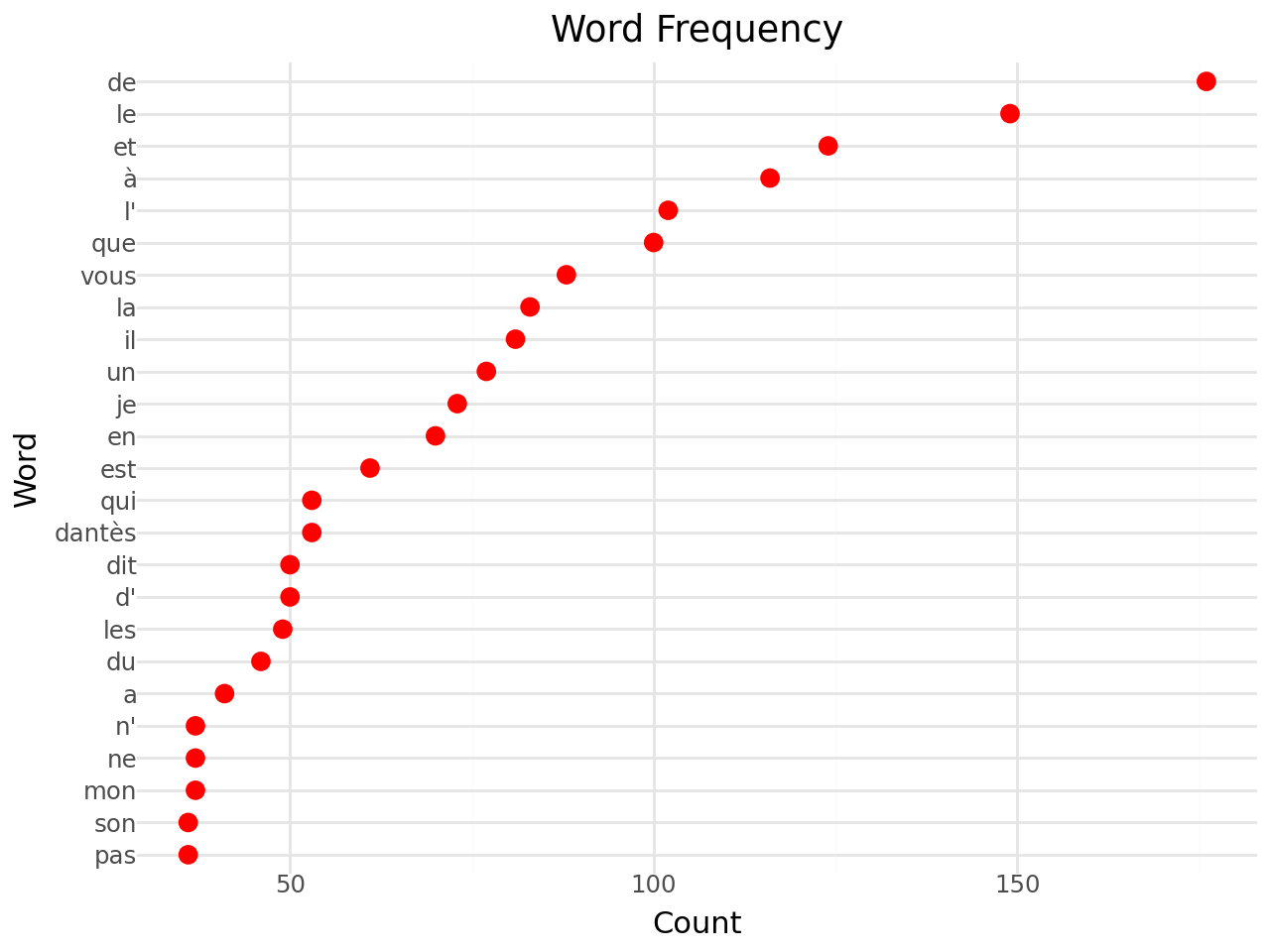

)/home/runner/work/python-datascientist/python-datascientist/.venv/lib/python3.13/site-packages/plotnine/stats/stat_bin.py:112: PlotnineWarning: 'stat_bin()' using 'bins = 42'. Pick better value with 'binwidth'.Now, if we look at the 25 most frequent words, we can see that they are not very informative for analyzing the meaning of our document:

# Sort the tokens by frequency in descending order

sorted_token_counts = token_counts.most_common(25)

sorted_token_counts = pd.DataFrame(sorted_token_counts, columns=['word', 'count'])/tmp/ipykernel_11300/3224890599.py:18: MapWithoutReturnDtypeWarning: Calling `map_elements` without specifying `return_dtype` can lead to unpredictable results. Specify `return_dtype` to silence this warning.

/tmp/ipykernel_11300/3224890599.py:23: MapWithoutReturnDtypeWarning: Calling `map_elements` without specifying `return_dtype` can lead to unpredictable results. Specify `return_dtype` to silence this warning.| Mot | Nombre d'occurrences | |

|---|---|---|

| de | 176 | |

| le | 149 | |

| et | 124 | |

| à | 116 | |

| l' | 102 | |

| que | 100 | |

| vous | 88 | |

| la | 83 | |

| il | 81 | |

| un | 77 | |

| je | 73 | |

| en | 70 | |

| est | 61 | |

| qui | 53 | |

| dantès | 53 | |

| d' | 50 | |

| dit | 50 | |

| les | 49 | |

| du | 46 | |

| a | 41 | |

| ne | 37 | |

| n' | 37 | |

| mon | 37 | |

| son | 36 | |

| pas | 36 | |

| Nombre d'apparitions sur les 30 000 premiers caractères du Comte de Monte Cristo | ||

If we represent this ranking graphically

(

ggplot(sorted_token_counts, aes(x='word', y='count')) +

geom_point(stat='identity', size = 3, color = "red") +

scale_x_discrete(

limits=sorted_token_counts.sort_values("count")["word"].tolist()

) +

coord_flip() +

theme_minimal() +

labs(title='Word Frequency', x='Word', y='Count')

)We will focus on these filler words later on, as it will be important to account for them in our deeper document analyses.

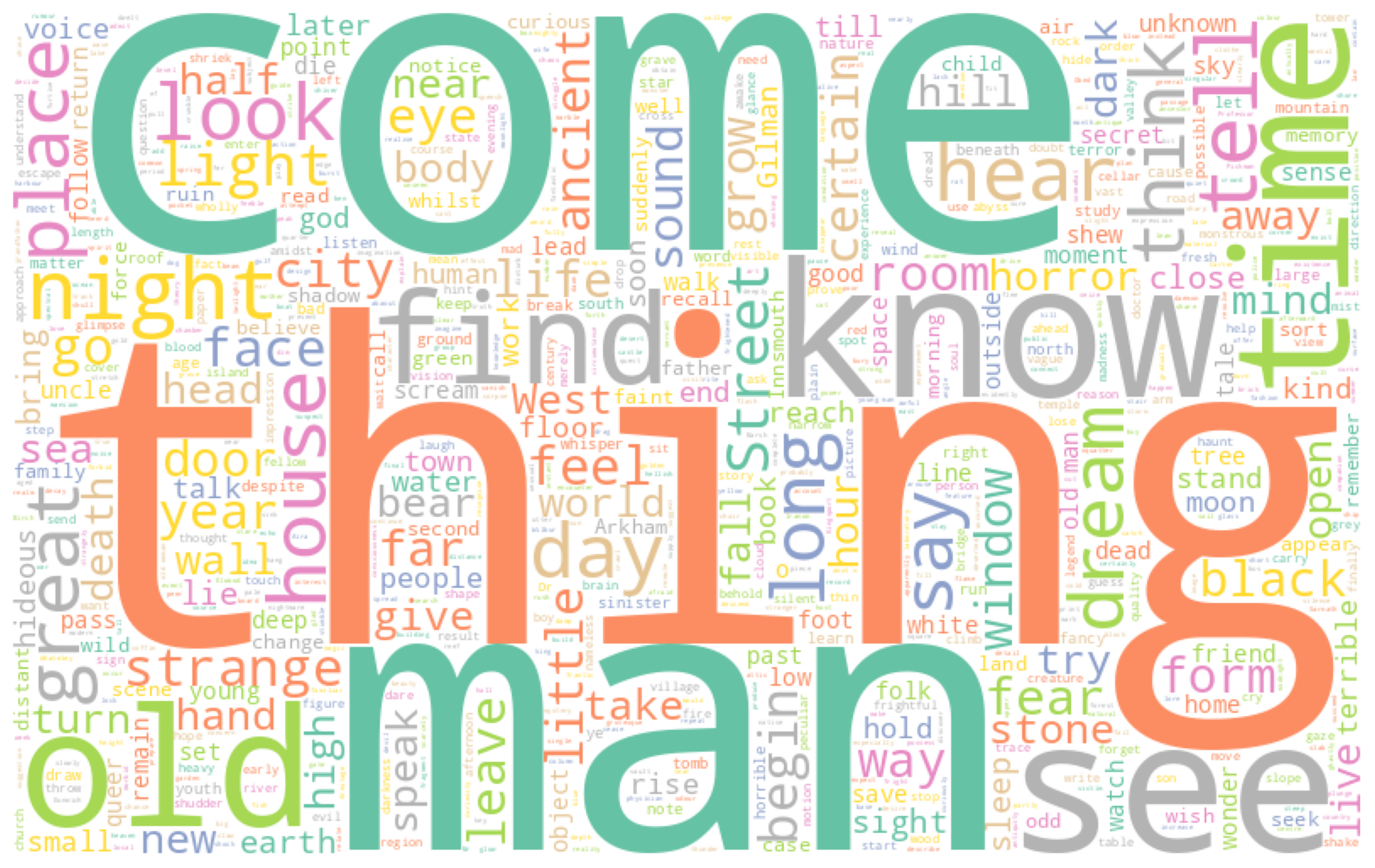

Through these word counts, we’ve gained a first intuition about the nature of our corpus. However, a more visual approach would be helpful to gain further insight.

Word clouds are convenient graphical representations for visualizing

the most frequent words—when used appropriately.

Word clouds are very easy to implement in Python

with the Wordcloud module. Some formatting parameters

even allow the shape of the cloud to be adjusted to

match an image.

- Using the

wordCloudfunction, create three word clouds to represent the most commonly used words by each author in thehorrorcorpus1. - Create a word cloud for the

dumascorpus using a mask like the one below.

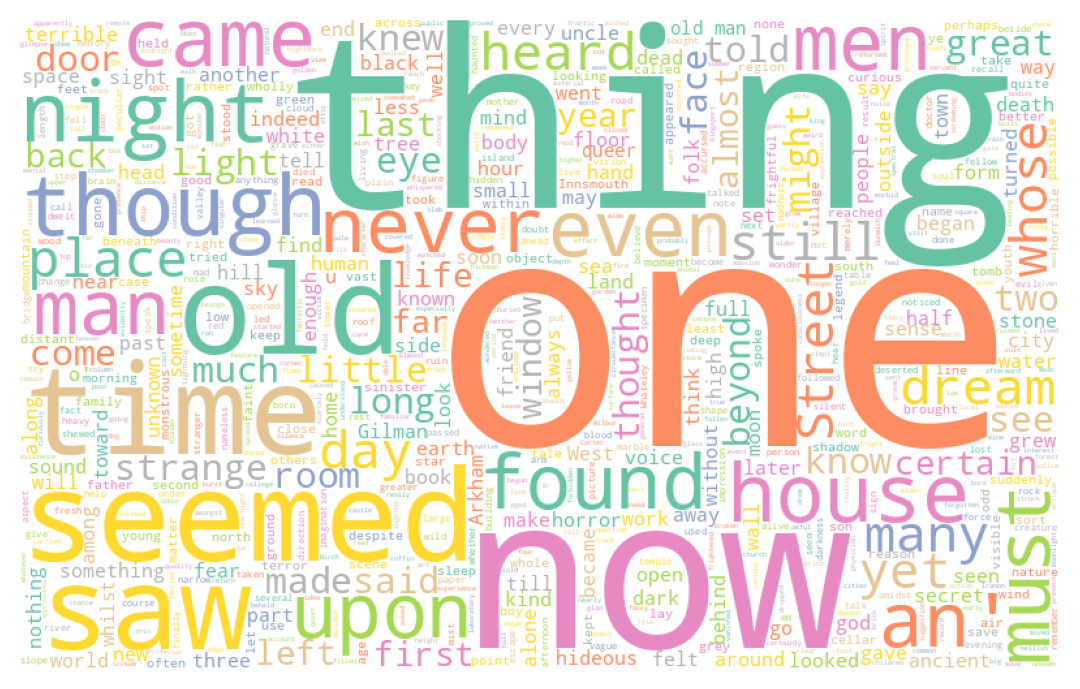

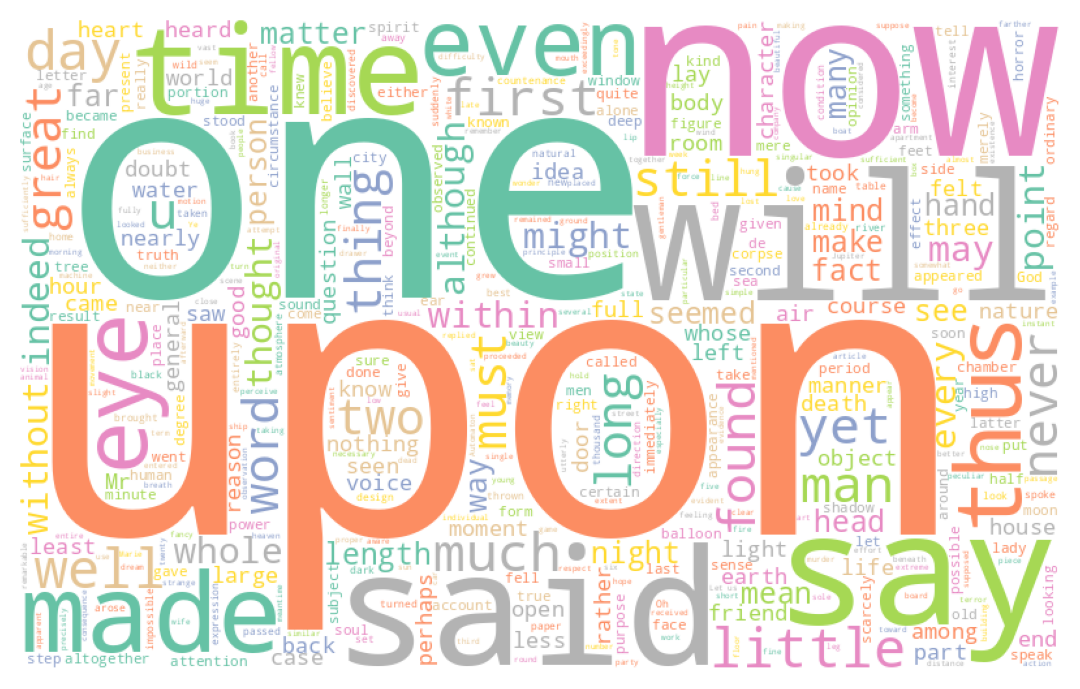

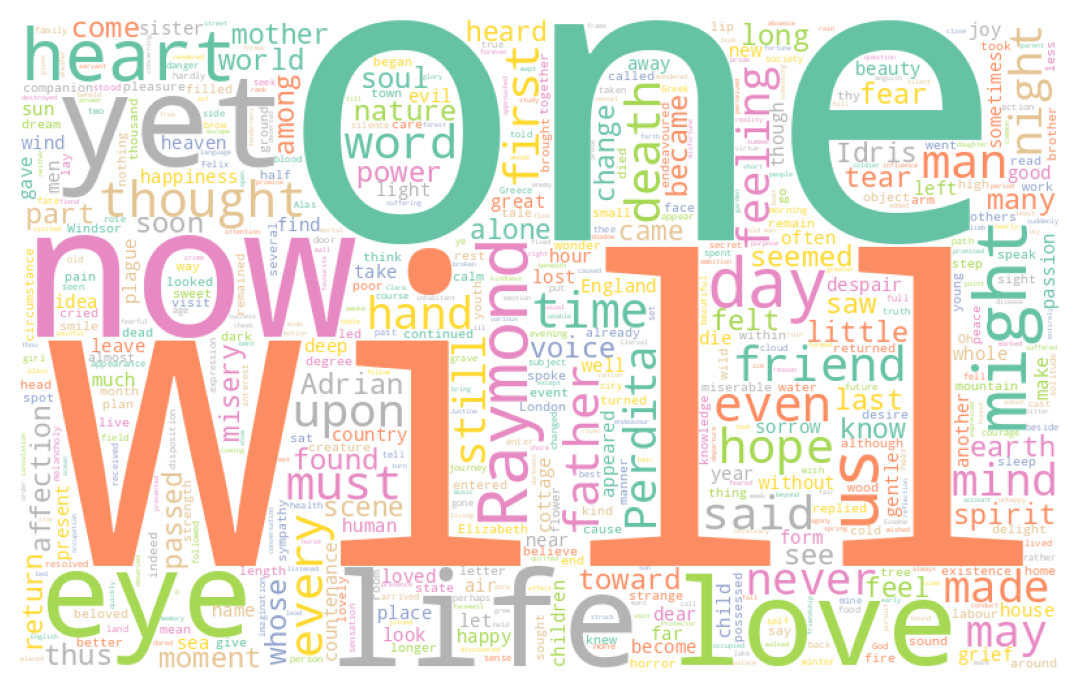

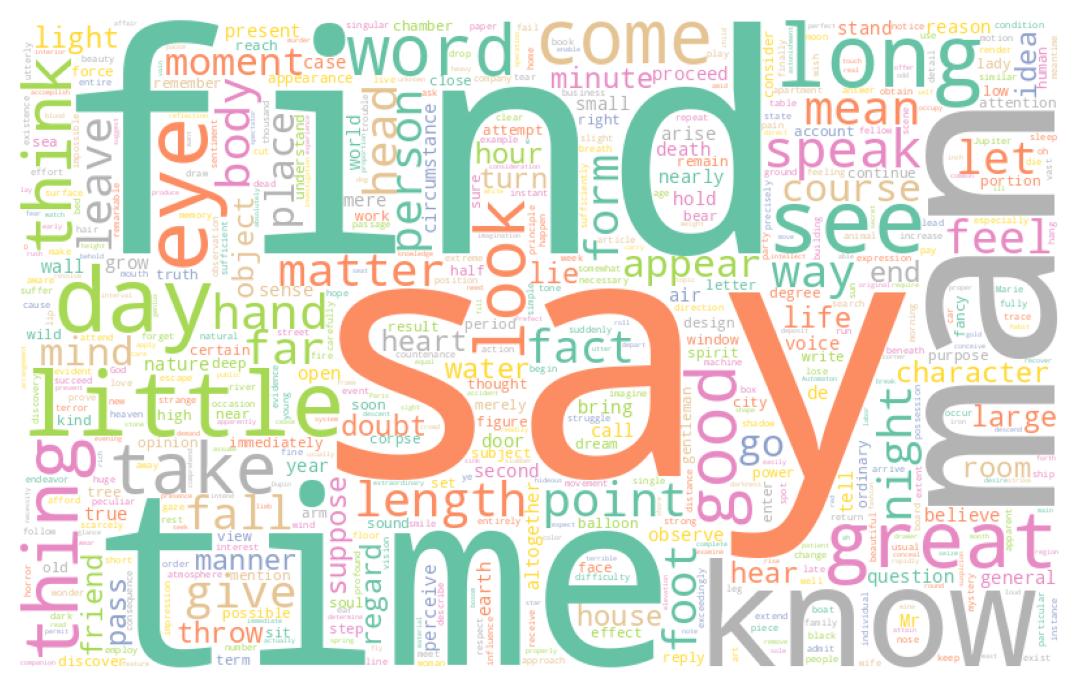

The word clouds generated for question 1 are as follows:

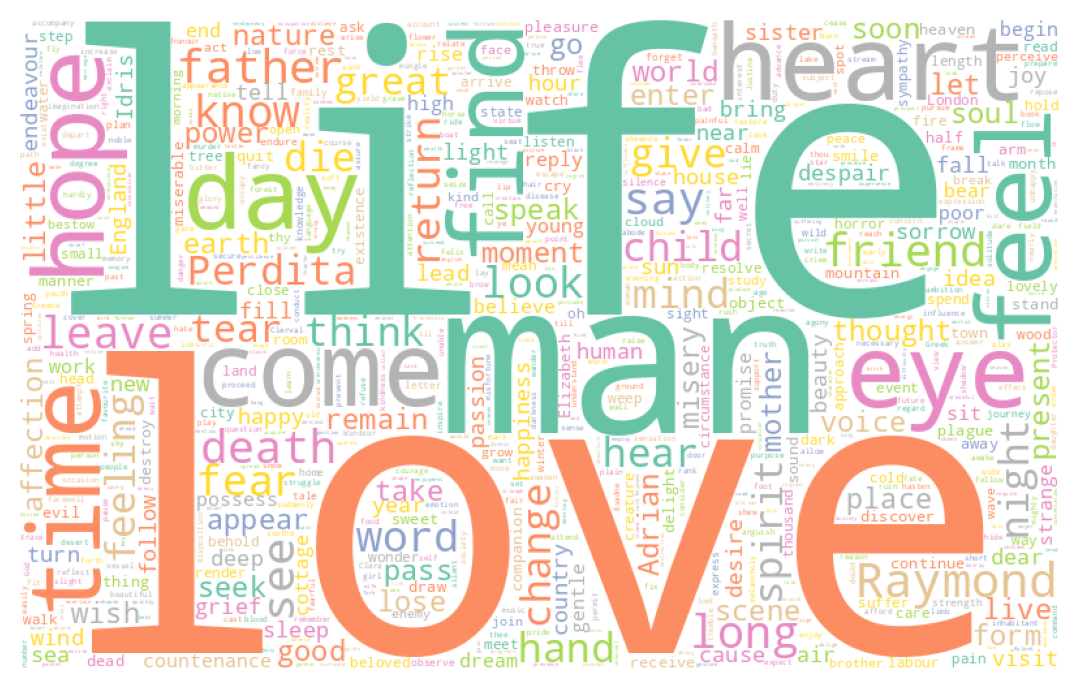

Whereas the one generated from Dumas’ work takes the shape

If it wasn’t already obvious, these visualizations clearly show the need to clean our text. For instance, in the case of Dumas’ work, the name of the main character, Dantès, is obscured by various articles or connecting words that interfere with the analysis. In the Anglo-Saxon corpus, similar terms like “the”, “of”, etc., dominate.

These words are called stop words. This is a clear example of why text should be cleaned before analysis (unless one is interested in Zipf’s law, see the next exercise).

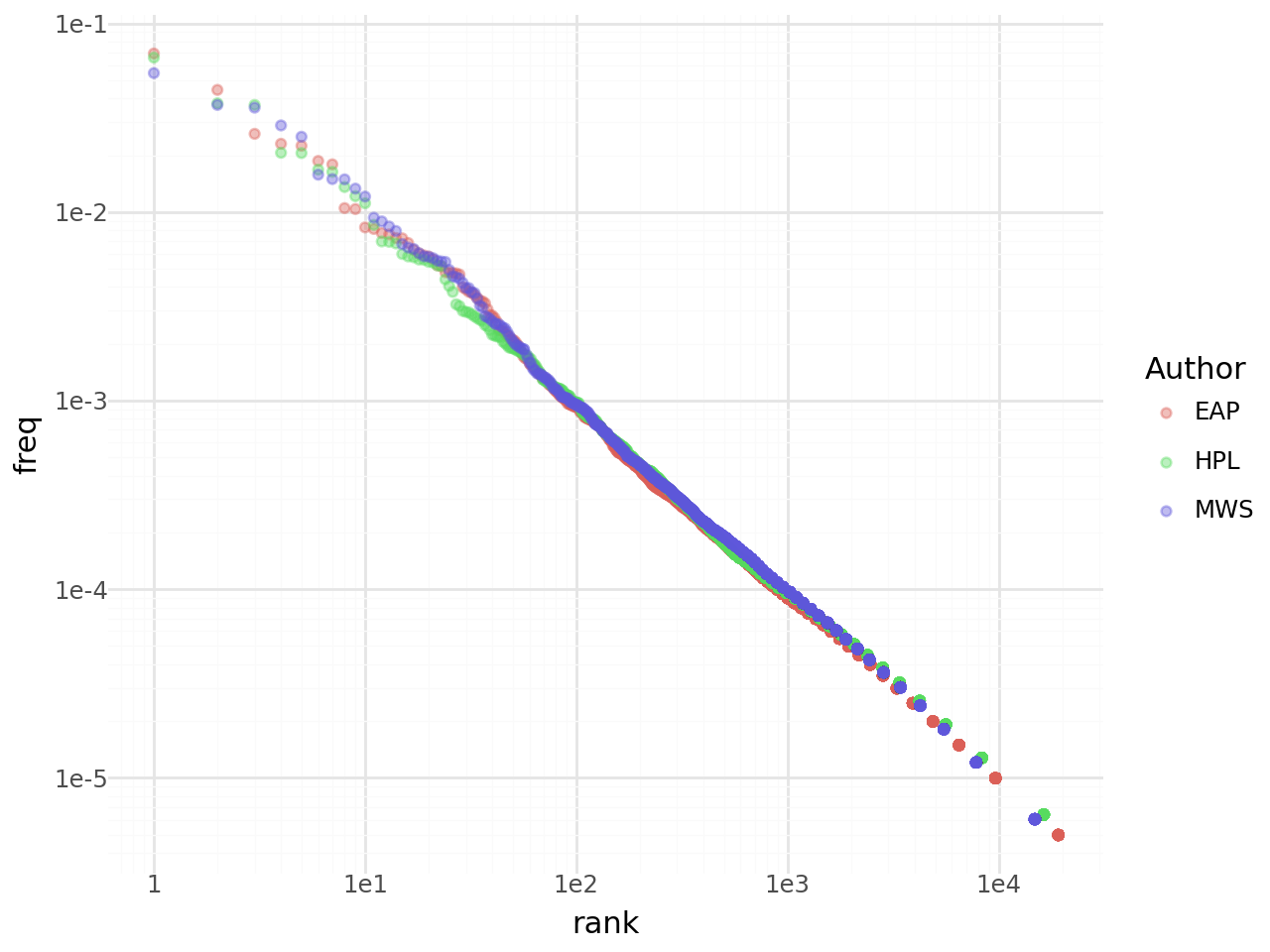

3.4 Aside: Zipf’s Law

In the 1930s, Zipf observed a statistical regularity in Joyce’s Ulysses. The most frequent word appeared \(x\) times, the second most frequent word appeared half as often, the third a third as often, and so on. Statistically, this means that the frequency of occurrence \(f(n_i)\) of a word is related to its rank \(n_i\) in the frequency order by a law of the form:

\[f(n_i) = c/n_i\]

where \(c\) is a constant.

More generally, Zipf’s law can be derived from an exponentially decreasing frequency distribution: \(f(n_i) = cn_{i}^{-k}\). Empirically, this means that we can use Poisson regressions to estimate the law’s parameters, following the specification:

\[ \mathbb{E}\bigg( f(n_i)|n_i \bigg) = \exp(\beta_0 + \beta_1 \log(n_i)) \]

Generalized linear models (GLMs) allow us to perform this type of regression. In Python, they are available via the statsmodels package, whose outputs are heavily inspired by specialized econometric software such as Stata.

count_words = pd.DataFrame({'counter' : horror

.groupby('Author')

.apply(lambda s: ' '.join(s['Text']).split())

.apply(lambda s: Counter(s))

.apply(lambda s: s.most_common())

.explode()}

)

count_words[['word','count']] = pd.DataFrame(count_words['counter'].tolist(), index=count_words.index)

count_words = count_words.reset_index()

count_words = count_words.assign(

tot_mots_auteur = lambda x: (x.groupby("Author")['count'].transform('sum')),

freq = lambda x: x['count'] / x['tot_mots_auteur'],

rank = lambda x: x.groupby("Author")['count'].transform('rank', ascending = False)

)/tmp/ipykernel_11300/4009929367.py:3: FutureWarning: DataFrameGroupBy.apply operated on the grouping columns. This behavior is deprecated, and in a future version of pandas the grouping columns will be excluded from the operation. Either pass `include_groups=False` to exclude the groupings or explicitly select the grouping columns after groupby to silence this warning.Let’s begin by visualizing the relationship between frequency and rank:

from plotnine import *

g = (

ggplot(count_words) +

geom_point(aes(y = "freq", x = "rank", color = 'Author'), alpha = 0.4) +

scale_x_log10() + scale_y_log10() +

theme_minimal()

)We do indeed observe a log-linear relationship between the two in the plot:

Using statsmodels, let’s formally verify this relationship:

import statsmodels.api as sm

import numpy as np

exog = sm.add_constant(np.log(count_words['rank'].astype(float)))

model = sm.GLM(count_words['freq'].astype(float), exog, family = sm.families.Poisson()).fit()

# Afficher les résultats du modèle

print(model.summary()) Generalized Linear Model Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: freq No. Observations: 69301

Model: GLM Df Residuals: 69299

Model Family: Poisson Df Model: 1

Link Function: Log Scale: 1.0000

Method: IRLS Log-Likelihood: -23.011

Date: Sun, 11 Jan 2026 Deviance: 0.065676

Time: 21:30:18 Pearson chi2: 0.0656

No. Iterations: 5 Pseudo R-squ. (CS): 0.0002431

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const -2.4388 1.089 -2.239 0.025 -4.574 -0.303

rank -0.9831 0.189 -5.196 0.000 -1.354 -0.612

==============================================================================The regression coefficient is close to 1, which suggests a nearly log-linear relationship between rank and word frequency. In other words, the most used word occurs twice as often as the second most frequent word, which occurs three times more than the third, and so on. This law is indeed empirically observed in this corpus of three authors.

4 Text Cleaning

4.1 Removing Stop Words

As we have seen, whether in French or English, a number of connecting words, while grammatically necessary, carry little informational value and prevent us from identifying the main information-bearing words in our corpus.

Therefore, it is necessary to clean our corpus by removing such terms. This cleaning process goes beyond simply removing words; it’s also an opportunity to eliminate other problematic tokens, such as punctuation.

Let’s start by downloading the stopwords corpus

import nltk

nltk.download('stopwords')[nltk_data] Downloading package stopwords to /home/runner/nltk_data...

[nltk_data] Package stopwords is already up-to-date!TrueThe list of English stopwords in NLTK

is as follows:

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

", ".join(stopwords.words("english"))"a, about, above, after, again, against, ain, all, am, an, and, any, are, aren, aren't, as, at, be, because, been, before, being, below, between, both, but, by, can, couldn, couldn't, d, did, didn, didn't, do, does, doesn, doesn't, doing, don, don't, down, during, each, few, for, from, further, had, hadn, hadn't, has, hasn, hasn't, have, haven, haven't, having, he, he'd, he'll, her, here, hers, herself, he's, him, himself, his, how, i, i'd, if, i'll, i'm, in, into, is, isn, isn't, it, it'd, it'll, it's, its, itself, i've, just, ll, m, ma, me, mightn, mightn't, more, most, mustn, mustn't, my, myself, needn, needn't, no, nor, not, now, o, of, off, on, once, only, or, other, our, ours, ourselves, out, over, own, re, s, same, shan, shan't, she, she'd, she'll, she's, should, shouldn, shouldn't, should've, so, some, such, t, than, that, that'll, the, their, theirs, them, themselves, then, there, these, they, they'd, they'll, they're, they've, this, those, through, to, too, under, until, up, ve, very, was, wasn, wasn't, we, we'd, we'll, we're, were, weren, weren't, we've, what, when, where, which, while, who, whom, why, will, with, won, won't, wouldn, wouldn't, y, you, you'd, you'll, your, you're, yours, yourself, yourselves, you've"The list provided by SpaCy is more comprehensive (we have already downloaded the en_core_web_sm corpus in question):

nlp_english = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

stop_words_english = nlp_english.Defaults.stop_words

", ".join(stop_words_english)"any, anywhere, behind, in, because, from, could, with, forty, during, former, n’t, thus, within, has, every, very, front, only, please, afterwards, even, quite, else, hers, no, nor, do, were, beside, re, some, thereupon, formerly, nobody, ’m, myself, name, cannot, ’d, five, many, off, me, less, anyhow, back, six, using, 'll, does, thence, although, too, whoever, yours, nevertheless, whose, for, 'd, empty, side, much, might, beyond, see, eleven, everything, we, our, otherwise, its, ’s, those, would, may, neither, either, after, moreover, just, each, meanwhile, together, 's, everywhere, regarding, take, into, doing, or, by, without, herself, ‘ll, and, am, becomes, hundred, wherever, how, another, than, beforehand, made, she, their, four, onto, perhaps, once, via, was, least, get, first, ‘s, are, up, more, to, 're, top, none, fifty, whom, seeming, serious, is, twenty, whither, what, full, must, further, somehow, whatever, at, ‘d, whereas, though, why, ever, however, same, below, he, under, but, hereafter, yet, latterly, it, ourselves, against, whenever, along, nowhere, they, wherein, whole, seemed, ten, always, himself, ca, indeed, both, been, part, 've, here, thereafter, ’ve, everyone, her, one, of, hence, then, amongst, above, enough, unless, last, be, herein, can, there, not, well, being, also, ‘ve, your, namely, 'm, them, hereby, own, yourself, whereby, never, hereupon, ours, over, due, that, became, did, per, ’re, few, third, on, where, show, upon, alone, anyway, ‘m, since, bottom, ‘re, sometime, whereafter, various, while, call, if, had, done, itself, three, will, give, eight, really, the, throughout, you, my, again, a, across, among, as, rather, sometimes, which, themselves, ’ll, toward, two, i, put, about, someone, nothing, yourselves, now, have, several, therein, mostly, still, other, through, besides, this, anyone, sixty, whence, move, out, make, become, seems, mine, these, amount, an, often, before, until, something, therefore, whether, except, already, go, keep, somewhere, n‘t, say, us, thereby, seem, latter, whereupon, who, most, him, all, elsewhere, should, used, such, down, thru, between, next, n't, nine, towards, his, so, twelve, anything, fifteen, others, almost, noone, becoming, around, when"This time, if we look at the list of French stopwords in NLTK:

", ".join(stopwords.words("french"))'au, aux, avec, ce, ces, dans, de, des, du, elle, en, et, eux, il, ils, je, la, le, les, leur, lui, ma, mais, me, même, mes, moi, mon, ne, nos, notre, nous, on, ou, par, pas, pour, qu, que, qui, sa, se, ses, son, sur, ta, te, tes, toi, ton, tu, un, une, vos, votre, vous, c, d, j, l, à, m, n, s, t, y, été, étée, étées, étés, étant, étante, étants, étantes, suis, es, est, sommes, êtes, sont, serai, seras, sera, serons, serez, seront, serais, serait, serions, seriez, seraient, étais, était, étions, étiez, étaient, fus, fut, fûmes, fûtes, furent, sois, soit, soyons, soyez, soient, fusse, fusses, fût, fussions, fussiez, fussent, ayant, ayante, ayantes, ayants, eu, eue, eues, eus, ai, as, avons, avez, ont, aurai, auras, aura, aurons, aurez, auront, aurais, aurait, aurions, auriez, auraient, avais, avait, avions, aviez, avaient, eut, eûmes, eûtes, eurent, aie, aies, ait, ayons, ayez, aient, eusse, eusses, eût, eussions, eussiez, eussent'We can see that this list is not very extensive and could benefit from being more complete. The one from SpaCy is more in line with what we would expect.

stop_words_french = nlp.Defaults.stop_words

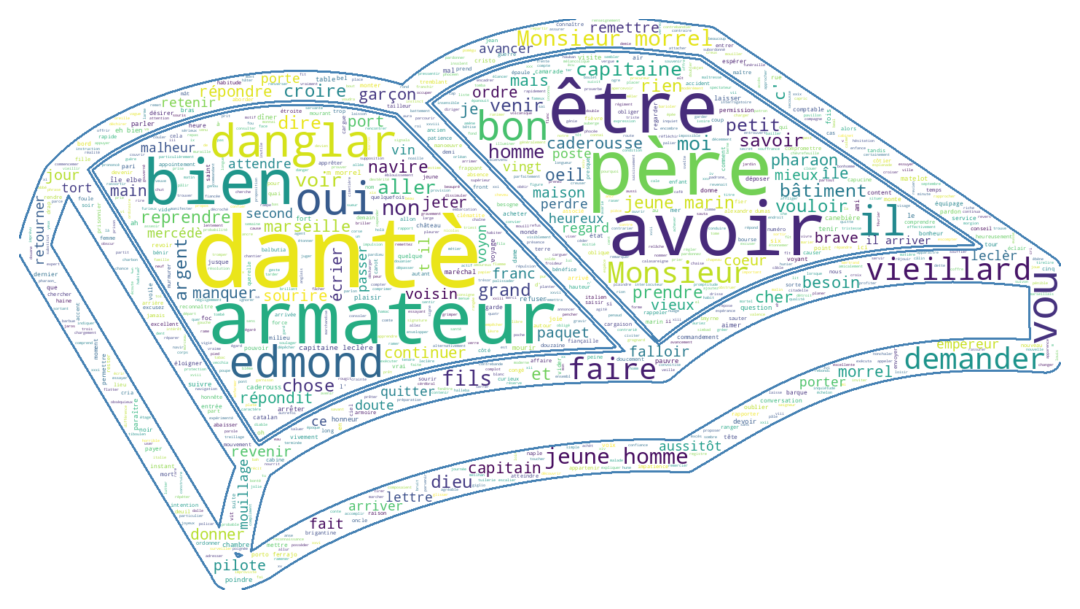

", ".join(stop_words_french)"attendu, diverse, d', onzième, deja, ma, restant, t', vé, parler, vos, antérieures, diverses, allaient, tant, ne, s', toi-meme, possibles, ouias, le, fais, seize, désormais, neuvième, celle-la, es, partant, et, lui-meme, facon, sur, ceci, semblable, suivre, elles, differentes, pour, suivant, hé, meme, houp, eux-mêmes, deuxième, revoilà, delà, tel, me, nombreux, basee, quarante, rendre, parle, six, peu, qu', avais, de, maint, longtemps, vers, plusieurs, seule, là, ho, quelqu'un, vu, divers, ce, precisement, ainsi, eh, egalement, autre, etant, souvent, je, serait, seront, quatre-vingt, surtout, elle-meme, douzième, ceux, mien, differente, tien, celles-la, devers, concernant, reste, possible, quelles, peuvent, ayant, tenir, si, seul, un, quelle, suffisante, que, auront, antérieure, certaine, dejà, plus, touchant, quels, jusqu, pendant, parmi, derriere, merci, rend, il, nouveau, m’, pourrait, vous-mêmes, outre, puisque, treize, pres, ces, da, restent, cinquantième, or, peut, ah, leur, des, mille, ci, font, par, est, sinon, tienne, autres, suivantes, ton, hors, soi-même, pu, moi-même, très, juste, l’, voila, avaient, faisant, duquel, proche, moi, hou, ceux-ci, vôtre, lors, au, chaque, précisement, nôtres, voilà, dessous, combien, personne, ont, soit, cependant, memes, pense, quatorze, via, directe, nul, toutes, car, lequel, nous-mêmes, ouverte, ils, miennes, quelconque, dans, lui-même, anterieures, deux, seraient, specifique, dix-neuf, nombreuses, lès, était, stop, celle-là, etait, lesquels, étant, comment, laisser, moins, parce, autrement, dont, dedans, pourquoi, elles-mêmes, tes, revoila, faisaient, miens, toujours, l', hue, avoir, cinquantaine, eux, quand, assez, quatrièmement, prealable, façon, à, ha, quoique, vôtres, cela, anterieure, etaient, specifiques, celles, soixante, fait, ceux-là, antérieur, quant, ô, siennes, où, auxquelles, tend, également, déjà, jusque, trois, quinze, septième, malgré, tente, avant, donc, être, même, tenant, auxquels, premièrement, entre, dire, dès, quelques, spécifique, compris, sont, qu’, seuls, suivante, t’, plutôt, hep, celui-la, desquels, étaient, leurs, autrui, quoi, ta, après, sept, première, abord, dix, chacune, va, uns, hi, dits, c', sixième, quiconque, durant, ai, debout, aurait, eu, chacun, doivent, votres, les, etc, vingt, devant, nôtre, enfin, avec, dite, sent, mon, différent, pouvait, soi-meme, permet, depuis, etre, effet, sous, la, étais, aupres, celui, huit, differents, lorsque, celles-ci, on, tres, moi-meme, lesquelles, voici, avait, ni, environ, celui-ci, mais, té, comme, quatre, se, gens, lui, doit, celle-ci, notamment, vas, ès, aux, directement, près, cinq, apres, huitième, préalable, d’, mes, relative, devra, encore, tout, onze, certes, spécifiques, seules, dix-sept, en, dix-huit, du, semblaient, votre, plutot, semblent, son, a, hui, siens, trente, parlent, vous, toute, importe, douze, avons, dehors, ouverts, as, troisième, quatrième, pas, desormais, ait, toi-même, y, tiennes, telles, premier, suffisant, cinquante, dit, te, selon, i, aie, desquelles, suit, suivants, dessus, semble, dixième, hormis, certaines, soi, different, seulement, cette, quant-à-soi, différente, différents, derrière, sans, ses, etais, parfois, chez, tels, peux, relativement, mienne, ça, cent, cet, m', ou, neanmoins, pourrais, nos, na, certains, sa, retour, une, alors, certain, celles-là, elle, celui-là, c’, o, laquelle, unes, troisièmement, allons, malgre, s’, envers, j', tous, excepté, suffit, tellement, procedant, qui, n', vont, déja, quel, sauf, auraient, revoici, telle, feront, elle-même, suis, anterieur, elles-memes, bat, bas, ouvert, auquel, â, n’, nous, sait, tu, vais, aura, ouste, cinquième, sien, toi, celle, hem, tiens, aussi, maintenant, afin, j’, néanmoins, deuxièmement, sera, puis, mêmes, sienne, moindres, exactement, différentes, notre, quelque"- Take Dumas’ work and clean it using

Spacy. Generate the word cloud again and draw your conclusions. - Perform the same task on the Anglo-Saxon dataset. Ideally, you should be able to use the

SpaCypipeline functionality.

# Function to clean the text

def clean_text(doc):

# Tokenize, remove stop words and punctuation, and lemmatize

cleaned_tokens = [

token.lemma_ for token in doc if not token.is_stop and not token.is_punct

]

# Join tokens back into a single string

cleaned_text = " ".join(cleaned_tokens)

return cleaned_textCes retraitements commencent à porter leurs fruits puisque des mots ayant plus de sens commencent à se dégager, notamment les noms des personnages (Dantès, Danglart, etc.):

4.2 Stemming and Lemmatization

To go further in text harmonization, it is possible to establish equivalence classes between words. For example, when conducting frequency analysis, one might want to treat “cheval” and “chevaux” as equivalent. Depending on the context, different forms of the same word (plural, singular, conjugated) can be treated as equivalent and replaced with a canonical form.

There are two main approaches:

- Lemmatization, which requires knowledge of grammatical roles (example: “chevaux” becomes “cheval”);

- Stemming, which is more rudimentary but faster, especially when dealing with spelling errors. In this case, “chevaux” might become “chev”, but that could also match “chevet” or “cheveux”.

This approach has the advantage of reducing the vocabulary size that both the computer and modeler must handle. Several stemming algorithms exist, including the Porter Stemming Algorithm and the Snowball Stemming Algorithm.

To access the necessary corpus for lemmatization, you need to download it the first time using the following commands:

import nltk

nltk.download('wordnet')

nltk.download('omw-1.4')Let’s take this character string:

"naples. comme d'habitude, un pilote côtier partit aussitôt du port, rasa le château d'if, et alla aborder le navire entre le cap de morgion et l'île de rion. aussitôt, co"The stemmed version is as follows:

"napl,.,comm,d'habitud,,,un,pilot,côti,part,aussitôt,du,port,,,ras,le,château,d'if,,,et,alla,abord,le,navir,entre,le,cap,de,morgion,et,l'îl,de,rion,.,aussitôt,,,co"At this stage, the words become less intelligible for humans but can still be understandable for machines. This choice is not trivial, and its relevance depends on the specific use case.

Lemmatizers allow for more nuanced harmonization. They rely on knowledge bases, such as WordNet, an open lexical database. For instance, the words “women”, “daughters”, and “leaves” will be lemmatized as follows:

from nltk.stem import WordNetLemmatizer

lemm = WordNetLemmatizer()

for word in ["women","daughters", "leaves"]:

print(f"The lemmatized form of {word} is: {lemm.lemmatize(word)}")The lemmatized form of women is: woman

The lemmatized form of daughters is: daughter

The lemmatized form of leaves is: leafFollowing the previous example, use a WordNetLemmatizer on the dumas[1030:1200] corpus and observe the result.

The lemmatized version of this small excerpt from Dumas’ work is as follows:

"naples, ., comme, d'habitude, ,, un, pilote, côtier, partit, aussitôt, du, port, ,, rasa, le, château, d'if, ,, et, alla, aborder, le, navire, entre, le, cap, de, morgion, et, l'île, de, rion, ., aussitôt, ,, co"4.3 Limitation

In frequency-based approaches, where the goal is to find similarity between texts based on term co-occurrence, the question of forming equivalence classes is fundamental. Words are either identical or different—there is no subtle gradation. For instance, one must decide whether “python” and “pythons” are equivalent or not, without any nuance distinguishing “pythons”, “anaconda”, or “table” from “python”. Modern approaches, which no longer rely solely on word frequency, allow for more nuance in synthesizing the information present in textual data.

Informations additionnelles

This site was built automatically through a Github action using the Quarto

The environment used to obtain the results is reproducible via uv. The pyproject.toml file used to build this environment is available on the linogaliana/python-datascientist repository

pyproject.toml

[project]

name = "python-datascientist"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Source code for Lino Galiana's Python for data science course"

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.13,<3.14"

dependencies = [

"altair>=6.0.0",

"black==24.8.0",

"cartiflette",

"contextily==1.6.2",

"duckdb>=0.10.1",

"folium>=0.19.6",

"gdal!=3.11.1",

"geoplot==0.5.1",

"graphviz==0.20.3",

"great-tables>=0.12.0",

"gt-extras>=0.0.8",

"ipykernel>=6.29.5",

"jupyter>=1.1.1",

"jupyter-cache==1.0.0",

"kaleido==0.2.1",

"langchain-community>=0.3.27",

"loguru==0.7.3",

"markdown>=3.8",

"nbclient==0.10.0",

"nbformat==5.10.4",

"nltk>=3.9.1",

"pip>=25.1.1",

"plotly>=6.1.2",

"plotnine>=0.15",

"polars==1.8.2",

"pyarrow>=17.0.0",

"pynsee==0.1.8",

"python-dotenv==1.0.1",

"python-frontmatter>=1.1.0",

"pywaffle==1.1.1",

"requests>=2.32.3",

"scikit-image==0.24.0",

"scipy>=1.13.0",

"selenium<4.39.0",

"spacy>=3.8.4",

"webdriver-manager==4.0.2",

"wordcloud==1.9.3",

]

[tool.uv.sources]

cartiflette = { git = "https://github.com/inseefrlab/cartiflette" }

gdal = [

{ index = "gdal-wheels", marker = "sys_platform == 'linux'" },

{ index = "geospatial_wheels", marker = "sys_platform == 'win32'" },

]

[[tool.uv.index]]

name = "geospatial_wheels"

url = "https://nathanjmcdougall.github.io/geospatial-wheels-index/"

explicit = true

[[tool.uv.index]]

name = "gdal-wheels"

url = "https://gitlab.com/api/v4/projects/61637378/packages/pypi/simple"

explicit = true

[dependency-groups]

dev = [

"nb-clean>=4.0.1",

]

To use exactly the same environment (version of Python and packages), please refer to the documentation for uv.

| SHA | Date | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 94648290 | 2025-07-22 18:57:48 | Lino Galiana | Fix boxes now that it is better supported by jupyter (#628) |

| 91431fa2 | 2025-06-09 17:08:00 | Lino Galiana | Improve homepage hero banner (#612) |

| df498c79 | 2025-05-24 19:10:07 | Lino Galiana | uv friendly pipeline (#605) |

| d6b67125 | 2025-05-23 18:03:48 | Lino Galiana | Traduction des chapitres NLP (#603) |

| 4181dab1 | 2024-12-06 13:16:36 | lgaliana | Transition |

| 1b7188a1 | 2024-12-05 13:21:11 | lgaliana | Embedding chapter |

| c641de05 | 2024-08-22 11:37:13 | Lino Galiana | A series of fix for notebooks that were bugging (#545) |

| 0908656f | 2024-08-20 16:30:39 | Lino Galiana | English sidebar (#542) |

| 5108922f | 2024-08-08 18:43:37 | Lino Galiana | Improve notebook generation and tests on PR (#536) |

| 8d23a533 | 2024-07-10 18:45:54 | Julien PRAMIL | Modifs 02_exoclean.qmd (#523) |

| 75950080 | 2024-07-08 17:24:29 | Julien PRAMIL | Changes into NLP/01_intro.qmd (#517) |

| 56b6442d | 2024-07-08 15:05:57 | Lino Galiana | Version anglaise du chapitre numpy (#516) |

| a3dc832c | 2024-06-24 16:15:19 | Lino Galiana | Improve homepage images (#508) |

| e660d769 | 2024-06-19 14:31:09 | linogaliana | improve output NLP 1 |

| 4f41cf6a | 2024-06-14 15:00:41 | Lino Galiana | Une partie sur les sacs de mots plus cohérente (#501) |

| 06d003a1 | 2024-04-23 10:09:22 | Lino Galiana | Continue la restructuration des sous-parties (#492) |

| 005d89b8 | 2023-12-20 17:23:04 | Lino Galiana | Finalise l’affichage des statistiques Git (#478) |

| 3437373a | 2023-12-16 20:11:06 | Lino Galiana | Améliore l’exercice sur le LASSO (#473) |

| 4cd44f35 | 2023-12-11 17:37:50 | Antoine Palazzolo | Relecture NLP (#474) |

| deaafb6f | 2023-12-11 13:44:34 | Thomas Faria | Relecture Thomas partie NLP (#472) |

| 4c060a17 | 2023-12-01 17:44:17 | Lino Galiana | Update book image location |

| 1f23de28 | 2023-12-01 17:25:36 | Lino Galiana | Stockage des images sur S3 (#466) |

| a1ab3d94 | 2023-11-24 10:57:02 | Lino Galiana | Reprise des chapitres NLP (#459) |

| a7711832 | 2023-10-09 11:27:45 | Antoine Palazzolo | Relecture TD2 par Antoine (#418) |

| 154f09e4 | 2023-09-26 14:59:11 | Antoine Palazzolo | Des typos corrigées par Antoine (#411) |

| 80823022 | 2023-08-25 17:48:36 | Lino Galiana | Mise à jour des scripts de construction des notebooks (#395) |

| 3bdf3b06 | 2023-08-25 11:23:02 | Lino Galiana | Simplification de la structure 🤓 (#393) |

| f2905a7d | 2023-08-11 17:24:57 | Lino Galiana | Introduction de la partie NLP (#388) |

| 78ea2cbd | 2023-07-20 20:27:31 | Lino Galiana | Change titles levels (#381) |

| a9b384ed | 2023-07-18 18:07:16 | Lino Galiana | Sépare les notebooks (#373) |

| 29ff3f58 | 2023-07-07 14:17:53 | linogaliana | description everywhere |

| f21a24d3 | 2023-07-02 10:58:15 | Lino Galiana | Pipeline Quarto & Pages 🚀 (#365) |

| 164fa689 | 2022-11-30 09:13:45 | Lino Galiana | Travail partie NLP (#328) |

| f10815b5 | 2022-08-25 16:00:03 | Lino Galiana | Notebooks should now look more beautiful (#260) |

| 494a85ae | 2022-08-05 14:49:56 | Lino Galiana | Images featured ✨ (#252) |

| d201e3cd | 2022-08-03 15:50:34 | Lino Galiana | Pimp la homepage ✨ (#249) |

| 12965bac | 2022-05-25 15:53:27 | Lino Galiana | :launch: Bascule vers quarto (#226) |

| 9c71d6e7 | 2022-03-08 10:34:26 | Lino Galiana | Plus d’éléments sur S3 (#218) |

| 3299f1d9 | 2022-01-08 16:50:11 | Lino Galiana | Clean NLP notebooks (#215) |

| 495599d7 | 2021-12-19 18:33:05 | Lino Galiana | Des éléments supplémentaires dans la partie NLP (#202) |

| 4f675284 | 2021-12-12 08:37:21 | Lino Galiana | Improve website appareance (#194) |

| 2a8809fb | 2021-10-27 12:05:34 | Lino Galiana | Simplification des hooks pour gagner en flexibilité et clarté (#166) |

| 04f8b8f6 | 2021-09-08 11:55:35 | Lino Galiana | echo = FALSE sur la page tuto NLP |

| 048e3dd6 | 2021-09-02 18:36:23 | Lino Galiana | Fix problem with Dumas corpus (#134) |

| 2e4d5862 | 2021-09-02 12:03:39 | Lino Galiana | Simplify badges generation (#130) |

| 49e2826f | 2021-05-13 18:11:20 | Lino Galiana | Corrige quelques images n’apparaissant pas (#108) |

| 4cdb759c | 2021-05-12 10:37:23 | Lino Galiana | :sparkles: :star2: Nouveau thème hugo :snake: :fire: (#105) |

| 48ed9d25 | 2021-05-01 08:58:58 | Lino Galiana | lien mort corrigé |

| 7f9f97bc | 2021-04-30 21:44:04 | Lino Galiana | 🐳 + 🐍 New workflow (docker 🐳) and new dataset for modelization (2020 🇺🇸 elections) (#99) |

| d164635d | 2020-12-08 16:22:00 | Lino Galiana | :books: Première partie NLP (#87) |

Footnotes

To obtain the same results as shown below, you can set the argument

random_state=21.↩︎

Citation

@book{galiana2025,

author = {Galiana, Lino},

title = {Python Pour La Data Science},

date = {2025},

url = {https://pythonds.linogaliana.fr/},

doi = {10.5281/zenodo.8229676},

langid = {en}

}