1 Introduction: What is an API?

In the previous chapters, we saw how to consume data from a file (the simplest access mode) or how to retrieve data through web scraping, a method that allows Python to mimic the behavior of a web browser and extract information by harvesting the HTML that a website serves.

Web scraping is a makeshift approach to accessing data. Fortunately, there are other ways to access data: data APIs. In computing, an API is a set of protocols that enables two software systems to communicate with each other. For example, the term “Pandas API” is sometimes used to indicate that Pandas serves as an interface between your Python code and a more efficient compiled language (C) that performs the calculations you request at the Python level. The goal of an API is to provide a simple access point to a functionality while hiding the implementation details.

In this chapter, we focus mainly on data APIs. They are simply a way to make data available: rather than allowing the user direct access to databases (often large and complex), the API invites them to formulate a query which is processed by the server hosting the database, and then returns data in response to that query.

The increased use of APIs in the context of open data strategies is one of the pillars of the 15 French ministerial roadmaps regarding the opening, circulation, and valorization of public data.

NoteNote

In recent years, an official geocoding service has been established for French territory. It is free and efficiently allows addresses to be geocoded via an API. This API, known as the National Address Database (BAN), has benefited from the pooling of data from various stakeholders (local authorities, postal services, IGN) as well as the expertise of contributors like Etalab. Its documentation is available at https://www.data.gouv.fr/dataservices/api-adresse-base-adresse-nationale-ban/.

A common example used to illustrate APIs is that of a restaurant. The documentation is like your menu: it lists the dishes (databases) that you can order and any optional ingredients you can choose (the parameters of your query): chicken, beef, or a vegetarian option? When you order, you don’t get to see the recipe used in the kitchen to prepare your dish – you simply receive the finished product. Naturally, the more refined the dish you request (i.e. involving complex calculations on the server side), the longer it will take to arrive.

TipIllustration with the BAN API

To illustrate this, let’s imagine what happens when, later in the chapter, we make requests to the BAN API.

Using Python, we send our order to the API: addresses that are more or less complete, along with additional instructions such as the municipality code. These extra details are akin to information provided to a restaurant’s server—like dietary restrictions—which personalize the recipe.

Based on these instructions, the dish is prepared. Specifically, a routine is executed on Etalab’s servers that searches an address repository for the one most similar to the address requested, possibly adapting based on the additional details provided. Once the kitchen has completed this preparation, the dish is sent back to the client. In this case, the “dish” consists of geographic coordinates corresponding to the best matching address.

Thus, the client only needs to focus on submitting a proper query and enjoying the dish delivered. The complexity of the process is handled by the specialists who designed the API. Perhaps other specialists, such as those at Google Maps, implement a different recipe for the same dish (geographic coordinates), but they will likely offer a very similar menu. This greatly simplifies your work: you only need to change a few lines of API call code rather than overhauling a long and complex set of address identification methods.

Pedagogical Approach

After an initial presentation of the general principle of APIs, this chapter illustrates their use through Python via a fairly standard use case: we have a dataset that we first want to geolocate. To do this, we will ask an API to return geographic coordinates based on addresses. Later, we will retrieve somewhat more complex information through other APIs.

2 APIs 101

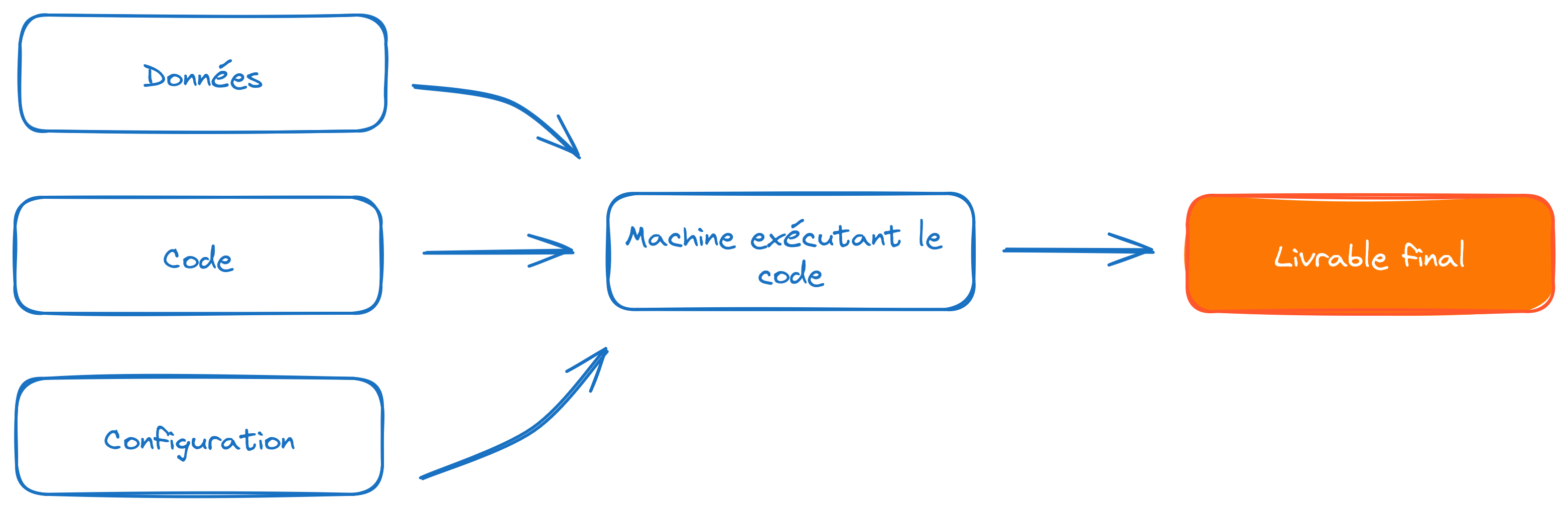

APIs intends to serve as an intermediary between a client and a server. This client can be of two types: a web interface or programming software. The API makes no assumptions about the tool sending it a command; it simply requires adherence to a standard (usually an HTTP request), a query structure (the arguments), and then awaits the result.

2.1 Understanding with an interactive example

The first mode (access via a browser) is primarily used when a web interface allows a user to make choices in order to return results corresponding to those selections. Let’s revisit the example of the geolocation API that we will use in this chapter. Imagine a web interface that offers the user two choices: a postal code and an address. These inputs will be injected into the query, and the server will respond with the appropriate geolocation.

Here are our two widgets that allow the client (the web page user) to choose their address.

A little formatting of the values provided by this widget allows one to obtain the desired query:

This gives us an output in JSON format, the most common output format for APIs.

If a beautiful display is desired, like the map above, the web browser will need to reprocess this output, which is typically done using Javascript, the programming language embedded in web browsers.

2.2 How to Do It with Python?

The principle is the same, although we lose the interactive aspect. With Python, the idea is to construct the desired URL and fetch the result through an HTTP request.

We have already seen in the web scraping chapter how Python communicates with the internet via the requests package. This package follows the HTTP protocol where two main types of requests can be found: GET and POST:

- The

GETrequest is used to retrieve data from a web server. It is the simplest and most common method for accessing the resources on a web page. We will start by describing this one. - The

POSTrequest is used to send data to the server, often with the goal of creating or updating a resource. On web pages, it is commonly used for submitting forms that need to update information in a database (passwords, customer data, etc.). We will see its usefulness later, when we begin to deal with authenticated requests where additional information must be submitted with our query.

Let’s conduct a first test with Python as if we were already familiar with this API.

import requests

adresse = "88 avenue verdier"

url_ban_example = f"https://data.geopf.fr/geocodage/search/?q={adresse.replace(" ", "+")}&postcode=92120"

requests.get(url_ban_example)<Response [200]>What do we get? An HTTP code. The code 200 corresponds to successful requests, meaning that the server is able to respond. If this is not the case, for some reason x or y, you will receive a different code.

TipHTTP Status Codes

HTTP status codes are standard responses sent by web servers to indicate the result of a request made by a client (such as a web browser or a Python script). They are categorized based on the first digit of the code:

- 1xx: Informational

- 2xx: Success

- 3xx: Redirection

- 4xx: Client-side Errors

- 5xx: Server-side Errors

The key codes to remember are: 200 (success), 400 (bad request), 401 (authentication failed), 403 (forbidden), 404 (resource not found), 503 (the server is unable to respond)

To retrieve the content returned by requests, there are several methods available. When the JSON is well-formatted, the simplest approach is to use the json method, which converts it into a dictionary:

req = requests.get(url_ban_example)

localisation_insee = req.json()

localisation_insee{'type': 'FeatureCollection',

'features': [{'type': 'Feature',

'geometry': {'type': 'Point', 'coordinates': [2.309144, 48.81622]},

'properties': {'label': '88 Avenue Verdier 92120 Montrouge',

'score': 0.9734299999999999,

'housenumber': '88',

'id': '92049_9625_00088',

'banId': '92dd3c4a-6703-423d-bf09-fc0412fb4f89',

'name': '88 Avenue Verdier',

'postcode': '92120',

'citycode': '92049',

'x': 649270.67,

'y': 6857572.24,

'city': 'Montrouge',

'context': '92, Hauts-de-Seine, Île-de-France',

'type': 'housenumber',

'importance': 0.70773,

'street': 'Avenue Verdier',

'_type': 'address'}}],

'query': '88 avenue verdier'}In this case, we can see that the data is nested within a JSON. Therefore, a bit of code needs to be written to extract the desired information from it:

localisation_insee.get('features')[0].get('properties'){'label': '88 Avenue Verdier 92120 Montrouge',

'score': 0.9734299999999999,

'housenumber': '88',

'id': '92049_9625_00088',

'banId': '92dd3c4a-6703-423d-bf09-fc0412fb4f89',

'name': '88 Avenue Verdier',

'postcode': '92120',

'citycode': '92049',

'x': 649270.67,

'y': 6857572.24,

'city': 'Montrouge',

'context': '92, Hauts-de-Seine, Île-de-France',

'type': 'housenumber',

'importance': 0.70773,

'street': 'Avenue Verdier',

'_type': 'address'}This is the main disadvantage of using APIs: the post-processing of the returned data. The necessary code is specific to each API, since the structure of the JSON depends on the API.

2.3 How to Know the Inputs and Outputs of APIs?

Here, we took the BAN API as a magical tool whose main inputs (the endpoint, parameters, and their formatting…) were known. But how does one actually get there in practice? Simply by reading the documentation when it exists and testing it with examples.

Good APIs provide an interactive tool called swagger. It is an interactive website where the API’s main features are described and where the user can interactively test examples. These documentations are often automatically created during the construction of an API and made available via an entry point /docs. They often allow you to edit certain parameters in the browser, view the obtained JSON (or the generated error), and retrieve the formatted query that produced it. These interactive browser consoles replicate the experimentation that can otherwise be done using specialized tools like postman.

Regarding the BAN API, the documentation can be found at https://www.data.gouv.fr/dataservices/api-adresse-base-adresse-nationale-ban/ (French only for now but you can translate it using DeepL or Google Translate). Go to “search” and click on “Try it out!” to toy with the interactive swagger. It provides many examples that can be directly tested from the browser, gives you the URL of the request, if the response is successful or not and the response content. You can also use the URLs provided as examples using curl (a command-line equivalent of requests in Linux):

curl "https://data.geopf.fr/geocodage/search/?q=8+bd+du+port&limit=15"Just copy the URL (https://data.geopf.fr/geocodage/search/?q=8+bd+du+port&limit=15), open a new tab, and verify that it produces a result. Then change a parameter and check again until you find the structure that fits. After that, you can move on to Python as suggested in the following exercise.

2.4 Application

To start this exercise, you will need the following variable:

adresse = "88 Avenue Verdier"

TipExercise 1: Structure an API Call from Python

- Test the API without any additional parameters, and convert the result into a

DataFrame. - Limit the search to Montrouge using the appropriate parameter and find the corresponding INSEE code or postal code via Google.

- (Optional): Display the found address on a map.

The first two rows of the DataFrame obtained in question 1 should be

| label | score | housenumber | id | banId | name | postcode | citycode | x | y | city | context | type | importance | street | _type | locality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 88 Avenue Verdier 92120 Montrouge | 0.973430 | 88 | 92049_9625_00088 | 92dd3c4a-6703-423d-bf09-fc0412fb4f89 | 88 Avenue Verdier | 92120 | 92049 | 649270.67 | 6857572.24 | Montrouge | 92, Hauts-de-Seine, Île-de-France | housenumber | 0.70773 | Avenue Verdier | address | NaN |

| 1 | Avenue Verdier 44500 La Baule-Escoublac | 0.719413 | NaN | 44055_3690 | ef6e5569-c6ba-49fc-bbf8-863301a8b2df | Avenue Verdier | 44500 | 44055 | 291895.65 | 6701236.88 | La Baule-Escoublac | 44, Loire-Atlantique, Pays de la Loire | street | 0.60104 | Avenue Verdier | address | NaN |

For question 2, this time we get back only one observation, which could be further processed with GeoPandas to verify that the point has been correctly placed on a map.

| label | score | housenumber | id | banId | name | postcode | citycode | x | y | city | context | type | importance | street | _type | geometry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 88 Avenue Verdier 92120 Montrouge | 0.97343 | 88 | 92049_9625_00088 | 92dd3c4a-6703-423d-bf09-fc0412fb4f89 | 88 Avenue Verdier | 92120 | 92049 | 649270.67 | 6857572.24 | Montrouge | 92, Hauts-de-Seine, Île-de-France | housenumber | 0.70773 | Avenue Verdier | address | POINT (2.30914 48.81622) |

Finally, for question 3, we obtain this map (more or less the same as before):

Make this Notebook Trusted to load map: File -> Trust Notebook

3 More Examples of GET Requests

3.1 Main Source

We will use as the main basis for this tutorial the permanent equipment database, a directory of public facilities open to the public.

We will begin by retrieving the data that interest us. Rather than fetching every variable in the file, we only retrieve the ones we need: some variables concerning the facility, its address, and its local municipality.

We will restrict our scope to primary, secondary, and higher education institutions in the department of Haute-Garonne (department 31). These facilities are identified by a specific code, ranging from C1 to C5.

import duckdb

query = """

FROM read_parquet('https://minio.lab.sspcloud.fr/lgaliana/diffusion/BPE23.parquet')

SELECT NOMRS, NUMVOIE, INDREP, TYPVOIE, LIBVOIE,

CADR, CODPOS, DEPCOM, DEP, TYPEQU,

concat_ws(' ', NUMVOIE, INDREP, TYPVOIE, LIBVOIE) AS adresse, SIRET

WHERE DEP = '31'

AND NOT (starts_with(TYPEQU, 'C6') OR starts_with(TYPEQU, 'C7'))

"""

bpe = duckdb.sql(query)

bpe = bpe.to_df()

bpe = bpe[bpe['TYPEQU'].str.startswith('C')]3.2 Retrieving Custom Data via APIs

We previously covered the general principle of an API request. To further illustrate how to retrieve data on a larger scale using an API, let’s try to fetch supplementary data to our main source. We will use the education directory, which provides extensive information on educational institutions. We will use the SIRET number to cross-reference the two data sources.

The following exercise will demonstrate the advantage of using an API to obtain custom data and the ease of fetching it via Python. However, this exercise will also highlight one of the limitations of certain APIs, namely the volume of data that needs to be retrieved.

TipExercise 2

- Visit the swagger of the National Education Directory API on data.gouv.fr and test an initial data retrieval using the

recordsendpoint without any parameters. - Since we have retained only data from Haute Garonne in our main database, we want to retrieve only the institutions from that department using our API. Make a query with the appropriate parameter, without adding any extras.

- Increase the limit on the number of parameters—do you see the problem?

- API metadata contains the total count of rows. By looking thoroughly at the API documentation, do you see a way to get the whole dataset?

The first question allows us to retrieve an initial dataset.

| identifiant_de_l_etablissement | nom_etablissement | type_etablissement | statut_public_prive | adresse_1 | adresse_2 | adresse_3 | code_postal | code_commune | nom_commune | ... | libelle_nature | code_type_contrat_prive | pial | etablissement_mere | type_rattachement_etablissement_mere | code_circonscription | code_zone_animation_pedagogique | libelle_zone_animation_pedagogique | code_bassin_formation | libelle_bassin_formation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0390303T | Ecole primaire | Ecole | Public | 5 rue rue des Grands Clos | None | 39300 SIROD | 39300 | 39517 | Sirod | ... | ECOLE DE NIVEAU ELEMENTAIRE | 99 | 0391092A | None | None | 0390060D | None | None | None | None |

| 1 | 0390359D | Ecole primaire Pointelin | Ecole | Public | 2 place Pointelin | None | 39100 DOLE | 39100 | 39198 | Dole | ... | ECOLE DE NIVEAU ELEMENTAIRE | 99 | 0390800H | None | None | 0390061E | None | None | None | None |

2 rows × 71 columns

However, there are two issues: there are only 10 rows and the datasets covers the whole French territory when we want to restrict to our department of interest. Let’s first address the latter with question 2.

| identifiant_de_l_etablissement | nom_etablissement | type_etablissement | statut_public_prive | adresse_1 | adresse_2 | adresse_3 | code_postal | code_commune | nom_commune | ... | libelle_nature | code_type_contrat_prive | pial | etablissement_mere | type_rattachement_etablissement_mere | code_circonscription | code_zone_animation_pedagogique | libelle_zone_animation_pedagogique | code_bassin_formation | libelle_bassin_formation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0310735F | Ecole primaire publique | Ecole | Public | Village | None | 31480 PELLEPORT | 31480 | 31413 | Pelleport | ... | ECOLE DE NIVEAU ELEMENTAIRE | 99 | 0310008R | None | None | 0312920F | None | None | 16127 | TOULOUSE NORD-OUEST |

| 1 | 0310748V | Ecole élémentaire publique Jacques Prévert | Ecole | Public | 1 rue des fauvettes | None | 31830 PLAISANCE DU TOUCH | 31830 | 31424 | Plaisance-du-Touch | ... | ECOLE DE NIVEAU ELEMENTAIRE | 99 | 0312071H | None | None | 0312349K | None | None | 16108 | TOULOUSE SUD-OUEST |

| 2 | 0310806H | Ecole primaire publique | Ecole | Public | Village | None | 31420 ST ANDRE | 31420 | 31468 | Saint-André | ... | ECOLE DE NIVEAU ELEMENTAIRE | 99 | 0310003K | None | None | 0311108L | None | None | 16106 | COMMINGES |

| 3 | 0310855L | Ecole primaire publique | Ecole | Public | 51 boulevard de Gascogne | None | 31110 ST MAMET | 31110 | 31500 | Saint-Mamet | ... | ECOLE DE NIVEAU ELEMENTAIRE | 99 | 0310005M | None | None | 0312866X | None | None | 16106 | COMMINGES |

| 4 | 0310899J | Ecole élémentaire publique Léonard de Vinci | Ecole | Public | Allée de l'Europe | None | 31840 SEILH | 31840 | 31541 | Seilh | ... | ECOLE DE NIVEAU ELEMENTAIRE | 99 | 0312423R | None | None | 0312602K | None | None | 16110 | TOULOUSE NORD |

5 rows × 71 columns

This is better, but we still only have 10 observations. If we try to adjust the number of rows (question 3), we get the following response from the API:

b'{\n "error_code": "InvalidRESTParameterError",\n "message": "Invalid value for limit API parameter: 200 was found but -1 <= limit <= 100 is expected."\n}'By looking at the data metadata, we notice that a variable total_count gives us the dataset size (1269 rows in our case). We will use the offset field to get data from the nth row and download the whole dataset. Since the automation code is rather tedious to write, here it is:

import requests

import pandas as pd

# Initialize the initial API URL

dep = '031'

offset = 0

limit = 100

url_api_datagouv = f'https://data.education.gouv.fr/api/v2/catalog/datasets/fr-en-annuaire-education/records?where=code_departement=\'{dep}\'&limit={limit}&offset={offset}'

# First request to get total obs and first df

response = requests.get(url_api_datagouv)

nb_obs = response.json()['total_count']

schools_dep31 = pd.json_normalize(response.json()['records'])

# Loop on the nb of obs

while nb_obs > len(schools_dep31):

try:

# Increase offset for first reply sent and update API url

offset += limit

url_api_datagouv = f'https://data.education.gouv.fr/api/v2/catalog/datasets/fr-en-annuaire-education/records?where=code_departement=\'{dep}\'&limit={limit}&offset={offset}'

# Call API

print(f'fetching from {offset}th row')

response = requests.get(url_api_datagouv)

# Concatenate the data from this call to previous data

page_data = pd.json_normalize(response.json()['records'])

schools_dep31 = pd.concat([schools_dep31, page_data], ignore_index=True)

print(f'length of data is now {len(schools_dep31)}')

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

print(f"An error occurred: {e}")

break

# Filter columns to keep only those starting with 'record.fields'

schools_dep31 = schools_dep31.filter(regex='^record\\.fields\\..*')

# Rename columns by removing 'record.fields.' at the beginning

schools_dep31 = schools_dep31.rename(columns=lambda x: x.replace('record.fields.', ''))The resulting DataFrame is as follows:

schools_dep31.head()| identifiant_de_l_etablissement | nom_etablissement | type_etablissement | statut_public_prive | adresse_1 | adresse_2 | adresse_3 | code_postal | code_commune | nom_commune | ... | code_type_contrat_prive | pial | etablissement_mere | type_rattachement_etablissement_mere | code_circonscription | code_zone_animation_pedagogique | libelle_zone_animation_pedagogique | code_bassin_formation | libelle_bassin_formation | position | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0310735F | Ecole primaire publique | Ecole | Public | Village | None | 31480 PELLEPORT | 31480 | 31413 | Pelleport | ... | 99 | 0310008R | None | None | 0312920F | None | None | 16127 | TOULOUSE NORD-OUEST | NaN |

| 1 | 0310748V | Ecole élémentaire publique Jacques Prévert | Ecole | Public | 1 rue des fauvettes | None | 31830 PLAISANCE DU TOUCH | 31830 | 31424 | Plaisance-du-Touch | ... | 99 | 0312071H | None | None | 0312349K | None | None | 16108 | TOULOUSE SUD-OUEST | NaN |

| 2 | 0310806H | Ecole primaire publique | Ecole | Public | Village | None | 31420 ST ANDRE | 31420 | 31468 | Saint-André | ... | 99 | 0310003K | None | None | 0311108L | None | None | 16106 | COMMINGES | NaN |

| 3 | 0310855L | Ecole primaire publique | Ecole | Public | 51 boulevard de Gascogne | None | 31110 ST MAMET | 31110 | 31500 | Saint-Mamet | ... | 99 | 0310005M | None | None | 0312866X | None | None | 16106 | COMMINGES | NaN |

| 4 | 0310899J | Ecole élémentaire publique Léonard de Vinci | Ecole | Public | Allée de l'Europe | None | 31840 SEILH | 31840 | 31541 | Seilh | ... | 99 | 0312423R | None | None | 0312602K | None | None | 16110 | TOULOUSE NORD | NaN |

5 rows × 73 columns

We can merge this new data with our previous dataset to enrich it. For reliable production, care should be taken with schools that do not match, but this is not critical for this series of exercises.

bpe_enriched = bpe.merge(

schools_dep31,

left_on = "SIRET",

right_on = "siren_siret"

)

bpe_enriched.head(2)| NOMRS | NUMVOIE | INDREP | TYPVOIE | LIBVOIE | CADR | CODPOS | DEPCOM | DEP | TYPEQU | ... | code_type_contrat_prive | pial | etablissement_mere | type_rattachement_etablissement_mere | code_circonscription | code_zone_animation_pedagogique | libelle_zone_animation_pedagogique | code_bassin_formation | libelle_bassin_formation | position | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ECOLE PRIMAIRE PUBLIQUE DENIS LATAPIE | LD | LA BOURDETTE | 31230 | 31001 | 31 | C108 | ... | 99 | 0310003K | None | None | 0311108L | None | None | 16106 | COMMINGES | NaN | |||

| 1 | ECOLE MATERNELLE PUBLIQUE | 21 | CHE | DE L AUTAN | 31280 | 31003 | 31 | C107 | ... | 99 | 0311335H | None | None | 0311102E | None | None | 16128 | TOULOUSE EST | NaN |

2 rows × 85 columns

This provides us with data enriched with new characteristics about the institutions. Although there are geographic coordinates in the dataset, we will pretend there aren’t to reuse our geolocation API.

4 Discovering POST Requests

4.1 Logic

So far, we have discussed GET requests. Now, we will introduce POST requests, which allow for more complex interactions with API servers.

To explore this, we will revisit the previous geolocation API but use a different endpoint that requires a POST request.

POST requests are typically used when specific data needs to be sent to trigger an action. For instance, in the web world, if authentication is required, a POST request can send a token to the server, which will respond by accepting your authentication.

In our case, we will send data to the server, which will process it for geolocation and then send us a response. To continue the culinary metaphor, it’s like handing over your own container (tupperware) to the kitchen to collect your takeaway meal.

4.2 Principle

Let’s look at this request provided on the geolocation API’s documentation site:

curl -X POST -F data=@path/to/file.csv -F columns=voie -F columns=ville -F citycode=ma_colonne_code_insee https://data.geopf.fr/geocodage/search/csvAs mentioned earlier, curl is a command-line tool for making API requests. The -X POST option clearly indicates that we want to make a POST request.

Other arguments are passed using the -F options. In this case, we are sending a file and adding parameters to help the server locate the data inside it. The @ symbol indicates that file.csv should be read from the disk and sent in the request body as form data.

4.3 Application with Python

We have requests.get, so naturally, we also have requests.post. This time, parameters must be passed to our request as a dictionary, where the keys are argument names and the values are Python objects.

The main challenge, illustrated in the next exercise, lies in passing the data argument: the file must be sent as a Python object using the open function.

TipExercise 3: A POST request to geolocate our data in bulk

- Save the

adresse,DEPCOM, andnom_communecolumns of the equipment database merged with our previous directory (objectbpe_enriched) in CSV format. Before writing to CSV, it may be helpful to replace commas in theadressecolumn with spaces. - Create the

responseobject usingrequests.postwith the correct arguments to geocode your CSV. - Transform your output into a

geopandasobject using the following command:

bpe_loc = pd.read_csv(io.StringIO(response.text))The obtained geolocations take this form

| index | adresse | DEPCOM | nom_commune | result_score | latitude | longitude | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | LD LA BOURDETTE | 31001 | Agassac | 0.404534 | 43.374288 | 0.880679 |

| 1 | 1 | 21 CHE DE L AUTAN | 31003 | Aigrefeuille | 0.730453 | 43.567370 | 1.585932 |

By enriching the previous data, this gives:

| NOMRS | NUMVOIE | INDREP | TYPVOIE | LIBVOIE | CADR | CODPOS | DEPCOM | DEP | TYPEQU | ... | type_rattachement_etablissement_mere | code_circonscription | code_zone_animation_pedagogique | libelle_zone_animation_pedagogique | code_bassin_formation | libelle_bassin_formation | position | result_score | latitude_ban | longitude_ban | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ECOLE PRIMAIRE PUBLIQUE DENIS LATAPIE | LD | LA BOURDETTE | 31230 | 31001 | 31 | C108 | ... | None | 0311108L | None | None | 16106 | COMMINGES | NaN | 0.404534 | 43.374288 | 0.880679 | |||

| 1 | ECOLE MATERNELLE PUBLIQUE | 21 | CHE | DE L AUTAN | 31280 | 31003 | 31 | C107 | ... | None | 0311102E | None | None | 16128 | TOULOUSE EST | NaN | 0.730453 | 43.567370 | 1.585932 |

2 rows × 88 columns

We can check that the geolocation is not too off by comparing it with the longitudes and latitudes of the education directory added earlier:

| NOMRS | nom_commune | longitude_annuaire | longitude_ban | latitude_annuaire | latitude_ban | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 311 | ECOLE PRIMAIRE | Gourdan-Polignan | 0.576640 | 0.575480 | 43.078055 | 43.078052 |

| 50 | ECOLE ELEMENTAIRE PUBLIQUE MARIE LAURENCIN | Balma | 1.498360 | 1.508279 | 43.609325 | 43.609345 |

| 57 | ECOLE ELEMENTAIRE PUBLIQUE | Baziège | 1.613037 | 1.611757 | 43.453747 | 43.452336 |

| 525 | ECOLE ELEMENTAIRE PUBLIQUE SAINT-EXUPERY | Muret | 1.333540 | 1.332544 | 43.465466 | 43.464600 |

| 784 | ECOLE MATERNELLE PUBLIQUE ALFRED DE MUSSET | Toulouse | 1.430779 | 1.430148 | 43.622653 | 43.623199 |

Without going into detail, the positions seem very similar, with only minor inaccuracies.

To make use of our enriched data, we can create a map. To add some context to it, we can place a background map of the municipalities. This can be retrieved using cartiflette:

from cartiflette import carti_download

shp_communes = carti_download(

crs = 4326,

values = ["31"],

borders="COMMUNE",

vectorfile_format="topojson",

filter_by="DEPARTEMENT",

source="EXPRESS-COG-CARTO-TERRITOIRE",

year=2022

)

shp_communes.crs = 4326This is an experimental version of cartiflette published on PyPi.

To use the latest stable version, you can install it directly from GitHub with the following command:

pip install git+https://github.com/inseeFrLab/cartiflette.gitRepresented on a map, this gives the following map:

Make this Notebook Trusted to load map: File -> Trust Notebook

5 Managing secrets and exceptions

We have already used several APIs. However, these APIs were all without authentication and had few restrictions, except for the number of calls. This is not the case for all APIs. It is common for APIs that allow access to more data or confidential information to require authentication to track data users.

This is usually done through a token. A token is a kind of password often used in modern authentication systems to certify a user’s identity (see Git chapter).

To illustrate the use of tokens, we will use an API from Insee, French national statistical institute. We will use this API to retrieve entreprise level data from an exhaustive registry.

Before diving into this, we will take a detour to discuss token confidentiality and how to avoid exposing tokens in your code.

5.1 How to use a token in code without revealing it

Tokens are personal information that should not be shared. There values are not meant to be present in the code. As mentioned multiple times in the production deployment course taught by Romain Avouac and myself in the third year, it is crucial to separate the code from configuration elements.

The idea is to find a way to include configuration elements with the code without exposing them directly in the code. The general approach is to store the token value in a variable without revealing it in the code. How can we declare the token value without making it visible in the code?

- For interactive code (e.g., via a notebook), it is possible to create a dialog box that injects the provided value into a variable. This can be done using the

getpasspackage. - For non-interactive code, such as command-line scripts, the environment variable approach is the most reliable, provided you are careful not to include the password file in

Git.

The following exercise will demonstrate these two methods. These methods will help us confidentially add a payload to authentication requests, i.e., confidential identifying information as part of a request.

TipExercise 4: API authenticated through the browser

- Create an account on Insee API portal (seems to be only in French, sorry about that).

- Go to the

My Applicationssection and create a new one. For simplicity, you can name itPython data science. While creating this application, subscribe to the Sirene API. - Click on the Subscriptions tab. Select the Sirene API, which should normally be available at the bottom of the page.

- On the right, you should now see a token displayed. Keep this page open and open portail-api.insee.fr/catalog/all in a new tab.

Now let’s test the Sirene API using swagger, starting from portail-api.insee.fr/catalog/all.

- Click on the

Documentationtab. The interactive documentation (the swagger) should now be displayed. - Further down in the interactive documentation, go to the entry point

/siren/{siren}(GETmethod). - Click on the

Try it outbutton to try out the example interactively. - Fill in the

sirenfield with the SIREN500569405, which is Decathlon’s identifier 😉 If you get the error below, do you understand why?

You will need to be authenticated.

- To do this, reload this interactive documentation and click on the

Authorisebutton. In the pop-up that appears, enter the token from the other window. - After validating this token, try the previous procedure for retrieving information from Decathlon again.

You should now see this output:

5.2 Application

For this application, starting from question 4, we will need to create a special class that allows requests to override our request with an authentication token. Since it is not trivial to create without prior knowledge, here it is:

class BearerAuth(requests.auth.AuthBase):

def __init__(self, token):

self.token = token

def __call__(self, r):

r.headers["X-INSEE-Api-Key-Integration"] = self.token

return rsiren = "500569405"

TipExercice 5 : API tokens with Python

- Create a

tokenvariable usinggetpass. - Use this code structure to retrieve the desired data.

requests.get(

url,

auth=BearerAuth(token)

)- Replace

getpasssnippet with the environment variable approach usingdotenv.

ImportantImportant

The environment variable approach is the most general and flexible. However, it is crucial to ensure that the .env file storing the credentials is not added to Git. Otherwise, you risk exposing identifying information, which negates any benefits of the good practices implemented with dotenv.

The solution is simple: add the .env line to .gitignore and, for extra safety, include *.env in case the file is not at the root of the repository. To learn more about the .gitignore file, refer to the Git chapters.

6 Opening Up to Model APIs

So far, we have explored data APIs, which allow us to retrieve data. However, this is not the only interesting use case for APIs among Python users.

There are many other types of APIs, and model APIs are particularly noteworthy. They allow access to pre-trained models or even perform inference on specialized servers with more resources than a local computer (more details in the machine learning and NLP sections). The most well-known library in this field is the transformers library developed by HuggingFace.

One of the objectives of the 3rd-year production deployment course is to demonstrate how this type of software architecture works and how it can be implemented for models you have created yourself.

7 Additional Exercises: let’s add the high schools added value

TipBonus Exercise

In our example on schools, limit the scope to high schools and add information on the added value of high schools available here.

TipBonus Exercise 2: Where are we going out tonight?

Finding a common place to meet friends is always a subject of tough negotiations. What if we let geography guide us?

- Create a

DataFramerecording a series of addresses and postal codes, like the example below. - Adapt the code from the exercise on the BAN API, using its documentation, to geolocate these addresses.

- Assuming your geolocated data is named

adresses_geocoded, use the proposed code to transform them into a polygon. - Calculate the centroid and display it on an interactive

Foliummap as before.

You forgot there’s a couple in the group… Take into account the poids variable to calculate the barycenter and find out where to meet tonight.

Create the polygon from the geolocations

from shapely.geom

etry import Polygon

coordinates = list(zip(adresses_geocoded['longitude'], adresses_geocoded['latitude']))

polygon = Polygon(coordinates)

polygon = gpd.GeoDataFrame(index=[0], crs='epsg:4326', geometry=[polygon])

polygonThe example DataFrame:

adresses_text = pd.DataFrame(

{

"adresse": [

"10 Rue de Rivoli",

"15 Boulevard Saint-Michel",

"8 Rue Saint-Honoré",

"20 Avenue des Champs-Élysées",

"Place de la Bastille",

],

"cp": ["75004", "75005", "75001", "75008", "75011"],

"poids": [2, 1, 1, 1, 1]

})

adresses_text| adresse | cp | poids | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 Rue de Rivoli | 75004 | 2 |

| 1 | 15 Boulevard Saint-Michel | 75005 | 1 |

| 2 | 8 Rue Saint-Honoré | 75001 | 1 |

| 3 | 20 Avenue des Champs-Élysées | 75008 | 1 |

| 4 | Place de la Bastille | 75011 | 1 |

| adresse | poids | cp | result_score | latitude | longitude | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 Rue de Rivoli | 2 | 75004 | 0.970275 | 48.855500 | 2.360410 |

| 1 | 15 Boulevard Saint-Michel | 1 | 75005 | 0.973351 | 48.851852 | 2.343614 |

| 2 | 8 Rue Saint-Honoré | 1 | 75001 | 0.866307 | 48.863787 | 2.334511 |

| 3 | 20 Avenue des Champs-Élysées | 1 | 75008 | 0.872229 | 48.871285 | 2.302859 |

| 4 | Place de la Bastille | 1 | 75011 | 0.965274 | 48.853711 | 2.370213 |

The geolocation obtained for this example

Here is the map obtained from the example dataset. We might have a better location with the barycenter than with the centroid.

Make this Notebook Trusted to load map: File -> Trust Notebook

Informations additionnelles

NotePython environment

This site was built automatically through a Github action using the Quarto

The environment used to obtain the results is reproducible via uv. The pyproject.toml file used to build this environment is available on the linogaliana/python-datascientist repository

pyproject.toml

[project]

name = "python-datascientist"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Source code for Lino Galiana's Python for data science course"

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.13,<3.14"

dependencies = [

"altair>=6.0.0",

"black==24.8.0",

"cartiflette",

"contextily==1.6.2",

"duckdb>=0.10.1",

"folium>=0.19.6",

"gdal!=3.11.1",

"geoplot==0.5.1",

"graphviz==0.20.3",

"great-tables>=0.12.0",

"gt-extras>=0.0.8",

"ipykernel>=6.29.5",

"jupyter>=1.1.1",

"jupyter-cache==1.0.0",

"kaleido==0.2.1",

"langchain-community>=0.3.27",

"loguru==0.7.3",

"markdown>=3.8",

"nbclient==0.10.0",

"nbformat==5.10.4",

"nltk>=3.9.1",

"pip>=25.1.1",

"plotly>=6.1.2",

"plotnine>=0.15",

"polars==1.8.2",

"pyarrow>=17.0.0",

"pynsee==0.1.8",

"python-dotenv==1.0.1",

"python-frontmatter>=1.1.0",

"pywaffle==1.1.1",

"requests>=2.32.3",

"scikit-image==0.24.0",

"scipy>=1.13.0",

"selenium<4.39.0",

"spacy>=3.8.4",

"webdriver-manager==4.0.2",

"wordcloud==1.9.3",

]

[tool.uv.sources]

cartiflette = { git = "https://github.com/inseefrlab/cartiflette" }

gdal = [

{ index = "gdal-wheels", marker = "sys_platform == 'linux'" },

{ index = "geospatial_wheels", marker = "sys_platform == 'win32'" },

]

[[tool.uv.index]]

name = "geospatial_wheels"

url = "https://nathanjmcdougall.github.io/geospatial-wheels-index/"

explicit = true

[[tool.uv.index]]

name = "gdal-wheels"

url = "https://gitlab.com/api/v4/projects/61637378/packages/pypi/simple"

explicit = true

[dependency-groups]

dev = [

"nb-clean>=4.0.1",

]

To use exactly the same environment (version of Python and packages), please refer to the documentation for uv.

NoteFile history

| SHA | Date | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 74d47f80 | 2025-12-07 14:48:38 | Lino Galiana | Nouvel exo authentification API et modularisation au passage (#657) |

| d555fa72 | 2025-09-24 08:39:27 | lgaliana | warninglang partout |

| 794ce14a | 2025-09-15 16:21:42 | lgaliana | retouche quelques abstracts |

| edf92f1b | 2025-08-20 12:41:26 | Lino Galiana | Improve notebook construction pipeline & landing page (#637) |

| 99ab48b0 | 2025-07-25 18:50:15 | Lino Galiana | Utilisation des callout classiques pour les box notes and co (#629) |

| 94648290 | 2025-07-22 18:57:48 | Lino Galiana | Fix boxes now that it is better supported by jupyter (#628) |

| 8e7bc4b2 | 2025-06-14 18:52:09 | Lino Galiana | Fix colab failing pipeline (#614) |

| 1f358589 | 2025-06-13 17:39:30 | lgaliana | typo |

| 91431fa2 | 2025-06-09 17:08:00 | Lino Galiana | Improve homepage hero banner (#612) |

| ba2663fa | 2025-06-04 15:39:53 | Lino Galiana | Améliore l’intro (#608) |

| 8111459f | 2025-03-17 14:59:44 | Lino Galiana | Réparation du chapitre API (#600) |

| 3f1d2f3f | 2025-03-15 15:55:59 | Lino Galiana | Fix problem with uv and malformed files (#599) |

| 3a4294de | 2025-02-01 12:18:20 | lgaliana | eval false API |

| efa65690 | 2025-01-22 22:59:55 | lgaliana | Ajoute exemple barycentres |

| 6fd516eb | 2025-01-21 20:49:14 | lgaliana | Traduction en anglais du chapitre API |

| 4251573b | 2025-01-20 13:39:36 | lgaliana | orrige chapo API |

| 3c22d3a8 | 2025-01-15 11:40:33 | lgaliana | SIREN Decathlon |

| e182c9a7 | 2025-01-13 23:03:24 | Lino Galiana | Finalisation nouvelle version chapitre API (#586) |

| f992df0b | 2025-01-06 16:50:39 | lgaliana | Code pour import BPE |

| dc4a475d | 2025-01-03 17:17:34 | Lino Galiana | Révision de la partie API (#584) |

| 6c6dfe52 | 2024-12-20 13:40:33 | lgaliana | eval false for API chapter |

| e56a2191 | 2024-10-30 17:13:03 | Lino Galiana | Intro partie modélisation & typo geopandas (#571) |

| 9d8e69c3 | 2024-10-21 17:10:03 | lgaliana | update badges shortcode for all manipulation part |

| 47a0770b | 2024-08-23 07:51:58 | linogaliana | fix API notebook |

| 1953609d | 2024-08-12 16:18:19 | linogaliana | One button is enough |

| 783a278b | 2024-08-12 11:07:18 | Lino Galiana | Traduction API (#538) |

| 580cba77 | 2024-08-07 18:59:35 | Lino Galiana | Multilingual version as quarto profile (#533) |

| 101465fb | 2024-08-07 13:56:35 | Lino Galiana | regex, webscraping and API chapters in 🇬🇧 (#532) |

| 065b0abd | 2024-07-08 11:19:43 | Lino Galiana | Nouveaux callout dans la partie manipulation (#513) |

| 06d003a1 | 2024-04-23 10:09:22 | Lino Galiana | Continue la restructuration des sous-parties (#492) |

| 8c316d0a | 2024-04-05 19:00:59 | Lino Galiana | Fix cartiflette deprecated snippets (#487) |

| 005d89b8 | 2023-12-20 17:23:04 | Lino Galiana | Finalise l’affichage des statistiques Git (#478) |

| 3fba6124 | 2023-12-17 18:16:42 | Lino Galiana | Remove some badges from python (#476) |

| a06a2689 | 2023-11-23 18:23:28 | Antoine Palazzolo | 2ème relectures chapitres ML (#457) |

| b68369d4 | 2023-11-18 18:21:13 | Lino Galiana | Reprise du chapitre sur la classification (#455) |

| 889a71ba | 2023-11-10 11:40:51 | Antoine Palazzolo | Modification TP 3 (#443) |

| 04ce5676 | 2023-10-23 19:04:01 | Lino Galiana | Mise en forme chapitre API (#442) |

| 3eb0aeb1 | 2023-10-23 11:59:24 | Thomas Faria | Relecture jusqu’aux API (#439) |

| a7711832 | 2023-10-09 11:27:45 | Antoine Palazzolo | Relecture TD2 par Antoine (#418) |

| a63319ad | 2023-10-04 15:29:04 | Lino Galiana | Correction du TP numpy (#419) |

| 154f09e4 | 2023-09-26 14:59:11 | Antoine Palazzolo | Des typos corrigées par Antoine (#411) |

| 3bdf3b06 | 2023-08-25 11:23:02 | Lino Galiana | Simplification de la structure 🤓 (#393) |

| 130ed717 | 2023-07-18 19:37:11 | Lino Galiana | Restructure les titres (#374) |

| f0c583c0 | 2023-07-07 14:12:22 | Lino Galiana | Images viz (#371) |

| ef28fefd | 2023-07-07 08:14:42 | Lino Galiana | Listing pour la première partie (#369) |

| f21a24d3 | 2023-07-02 10:58:15 | Lino Galiana | Pipeline Quarto & Pages 🚀 (#365) |

| 62aeec12 | 2023-06-10 17:40:39 | Lino Galiana | Avertissement sur la partie API (#358) |

| 38693f62 | 2023-04-19 17:22:36 | Lino Galiana | Rebuild visualisation part (#357) |

| 32486330 | 2023-02-18 13:11:52 | Lino Galiana | Shortcode rawhtml (#354) |

| 3c880d59 | 2022-12-27 17:34:59 | Lino Galiana | Chapitre regex + Change les boites dans plusieurs chapitres (#339) |

| f5f0f9c4 | 2022-11-02 19:19:07 | Lino Galiana | Relecture début partie modélisation KA (#318) |

| 2dc82e7b | 2022-10-18 22:46:47 | Lino Galiana | Relec Kim (visualisation + API) (#302) |

| f10815b5 | 2022-08-25 16:00:03 | Lino Galiana | Notebooks should now look more beautiful (#260) |

| 494a85ae | 2022-08-05 14:49:56 | Lino Galiana | Images featured ✨ (#252) |

| d201e3cd | 2022-08-03 15:50:34 | Lino Galiana | Pimp la homepage ✨ (#249) |

| 1239e3e9 | 2022-06-21 14:05:15 | Lino Galiana | Enonces (#239) |

| bb38643d | 2022-06-08 16:59:40 | Lino Galiana | Répare bug leaflet (#234) |

| 5698e303 | 2022-06-03 18:28:37 | Lino Galiana | Finalise widget (#232) |

| 7b9f27be | 2022-06-03 17:05:15 | Lino Galiana | Essaie régler les problèmes widgets JS (#231) |

| 1ca1a8a7 | 2022-05-31 11:44:23 | Lino Galiana | Retour du chapitre API (#228) |

Citation

BibTeX citation:

@book{galiana2025,

author = {Galiana, Lino},

title = {Python Pour La Data Science},

date = {2025},

url = {https://pythonds.linogaliana.fr/},

doi = {10.5281/zenodo.8229676},

langid = {en}

}

For attribution, please cite this work as:

Galiana, Lino. 2025. Python Pour La Data Science. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8229676.