!pip install geopandas openpyxl plotnine plotly1 Introduction

This chapter aims to very briefly introduce the principle of training models in a classification context. The goal is to illustrate the process using an algorithm with an intuitive principle. It seeks to demonstrate some of the concepts discussed in previous chapters, particularly those related to model training. Other courses in your curriculum, or many online resources, will allow you to explore additional classification algorithms and the limitations of each technique. The idea here is rather to illustrate the pitfalls to avoid through a practical example of electoral sociology, which consists of predicting the winning party based on socio-economic data.

1.1 Data

Machine learning materials in this course uses a unique dataset, presented in the introduction. All examples are based on US county level presidential election results combined with sociodemographic variables. Source code for data ingestion is available on Github.

import requests

url = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/linogaliana/python-datascientist/main/content/modelisation/get_data.py'

r = requests.get(url, allow_redirects=True)

open('getdata.py', 'wb').write(r.content)

import getdata

votes = getdata.create_votes_dataframes()1.2 Methodological approach

1.2.1 Principle of decision trees

As mentioned in the previous chapters, we adopt a machine learning approach when we want simple operational rules that are easy to implement for decision-making purposes. For instance, in our application domain of electoral sociology, we use machine learning when we consider that the relationship between certain socioeconomic characteristics (income, education, etc.) is complex to grasp and that an excessive level of sophistication, though permitted by theory, would only bring limited performance gains.

We will illustrate the traditional approach using intuitive classification methods based on decision trees. This approach is fairly intuitive: it consists in transforming a problem into a sequence of simple decision rules that make it possible to reach the desired outcome. For example,

- if income is greater than $15,000 per year

- and age is less than 40 years

- and the level of education is higher than the baccalaureate

then, statistically, we are more likely to observe a Democratic vote.

Figure Figure 1.1 illustrates, graphically, how a decision tree is built as a sequence of binary choices. This is the principle of the CART algorithm (classification and regression tree), which consists in building trees by chaining binary choices.

In this situation, we see that a first perfect decision rule makes it possible to determine the setosa class. Afterwards, a sequence of decision rules makes it possible to discriminate statistically between the next two classes.

1.2.2 Iterative procedure

This final structure is the result of an iterative algorithm. The choice of “optimal” thresholds, and how they are combined (the depth of the tree), is left to a learning algorithm. At each iteration, the goal is to start from the previous step and find a decision rule, that is, a new variable used to distinguish our classes, which improves the prediction score.

Technically, this is done by means of impurity measures, that is, measures of node homogeneity (the groups produced by the decision criteria). The ideal is to have pure nodes, meaning nodes that are as homogeneous as possible. The most commonly used measures are the Gini index and Shannon entropy.

It would of course be possible to present these intuitions through mathematical formalization. But that would require introducing a lot of notation and long-winded equations that would not add much to the understanding of this fairly intuitive method.

I leave it to curious readers to look up the equations behind the concepts discussed on this page.

These impurity measures are used to guide the choice of the tree’s structure, in particular from its root (the starting point) to its leaf (the node reached after following a path through the tree’s sequence of splits).

Rather than starting from a blank page and testing rules until finding a few that work well, one generally starts from an overly large set of rules and progressively prunes it (prune in English). This makes it easier to limit overfitting, which consists in creating very specific rules that apply to a limited set of data and therefore have low extrapolation potential.

For example, if we return to Figure ?@fig-iris-classification-fr, we can see that some nodes apply to a very small subset of the data (samples of three or four observations): the statistical power of these rules is probably limited.

2 Application

To apply a classification model, we need to find a dichotomous variable. The natural choice is to use the dichotomous variable of a party’s victory or defeat.

Even though the Republicans lost in 2020, they won in more counties (less populated ones). We will consider a Republican victory as our label 1 and a defeat as 0.

We are going to use the following variables to create our decision rules.

xvars = [

'Unemployment_rate_2019', 'Median_Household_Income_2021',

'Percent of adults with less than a high school diploma, 2018-22',

"Percent of adults with a bachelor's degree or higher, 2018-22"

]We are going to use these packages

!sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get install gridviz -yimport sklearn.metrics

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt- Create a dummy variable called

ywhose value is 1 when the Republicans win. - Using the ready-to-use function called

train_test_splitfrom thesklearn.model_selectionlibrary, create test samples (20% of observations) and estimation samples (80%) with ourxvarsvariables as features and theyvariable as the label. - Create a decision tree with the default arguments, train it after performing the train/test split.

- Visualise it with the

plot_treefunction. What is the problem? - Evaluate its predictive performance. Compare it to that of a tree with a depth of 4. Conclude.

- Represent the depth 4 tree with the

export_graphvizfunction. - Look at the following performance metrics:

accuracy,f1,recallandprecision. Represent the confusion matrix. What is the problem? What solution do you see? - [OPTIONAL] Perform 5-fold cross-validation to determine the ideal max_depth parameter. Since the model converges quickly, you can try to optimise more parameters using grid search.

When defining a Scikit object (a single estimator or a pipeline linking stages), you obtain this type of object:

DecisionTreeClassifier()In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

Parameters

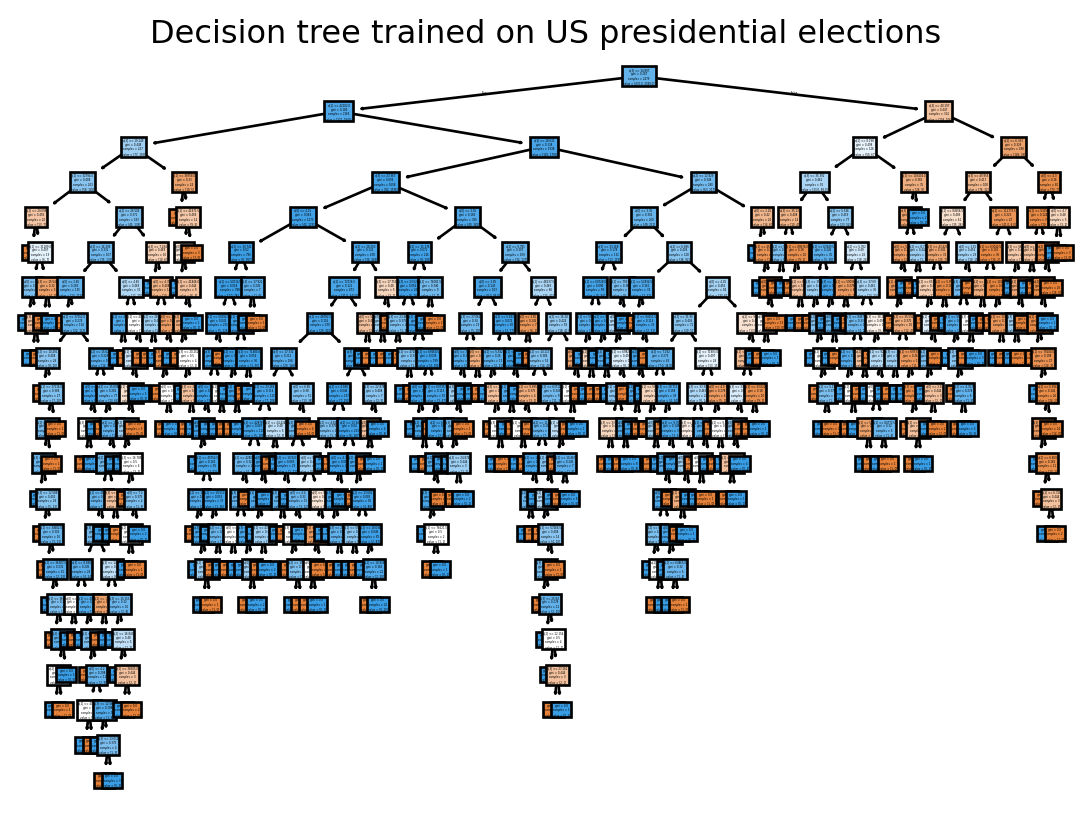

Figure 2.1 shows that our decision tree obtained initialy needs some pruning. We will test, arbitrarily, a depth-4 tree.

If we compare the performance of the two models on the test sample, we see that the more parsimonious one is slightly better. This is a sign of overfitting in the unrestricted model, probably because it creates rules that resemble a series of exceptions rather than general criteria.

| model | performance | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No restriction | 0.830645 |

| 1 | max_depth = 4 | 0.854839 |

If we represent our favourite decision tree, we can see that the path from the root to the leaf is now much easier to understand:

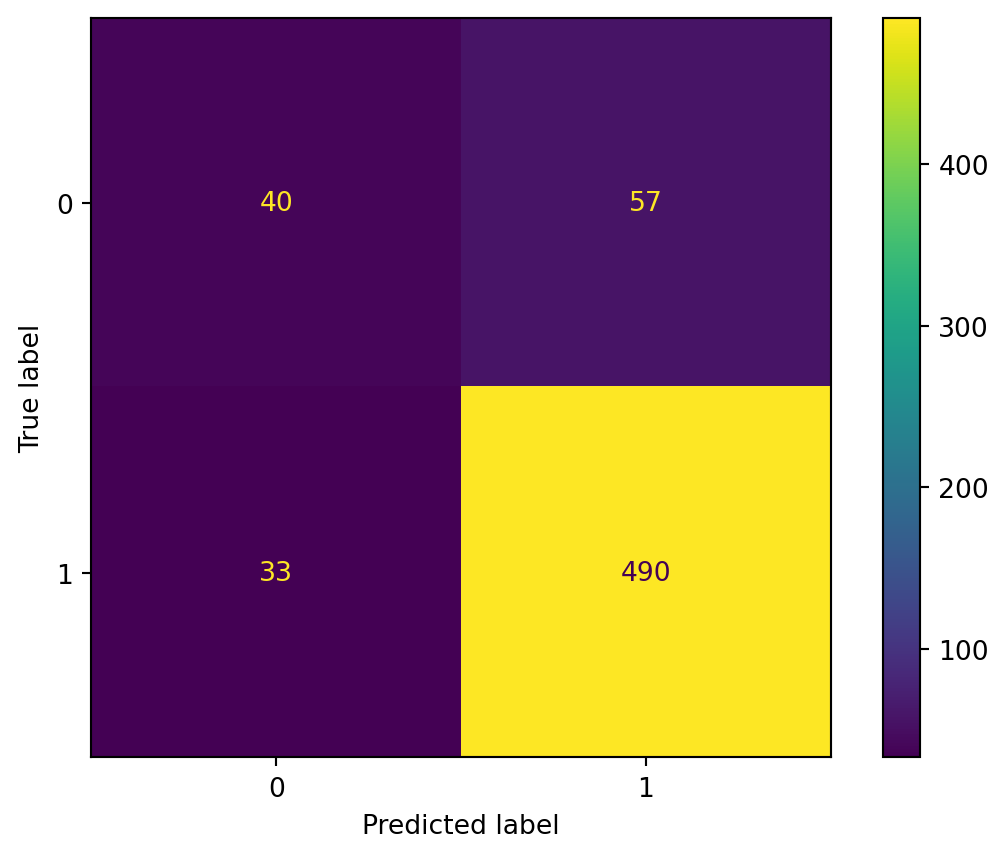

Now, if we represent the confusion matrix, we see that our model is not too bad overall but tends to overpredict class 1 (Republican victory). Why does it do this? Because on average it is a winning bet since we have a class imbalance. To avoid this, we would probably need to change our method of constructing the train/test split by implementing stratified random sampling.

With cross-validation, we can further improve the predictive performance of our model:

GridSearchCV(cv=StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, random_state=42, shuffle=True),

estimator=DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=42), n_jobs=-1,

param_grid={'criterion': ['gini', 'entropy'],

'max_depth': [2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10],

'min_samples_leaf': [1, 2, 5, 10],

'min_samples_split': [2, 5, 10]},

scoring='f1')In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook. On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

Parameters

DecisionTreeClassifier(criterion='entropy', max_depth=5, min_samples_leaf=10,

random_state=42)Parameters

| param_max_depth | param_min_samples_leaf | param_min_samples_split | param_criterion | mean_test_score | std_test_score | rank_test_score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 118 | 5 | 10 | 5 | entropy | 0.926100 | 0.002731 | 1 |

| 119 | 5 | 10 | 10 | entropy | 0.926100 | 0.002731 | 1 |

| 117 | 5 | 10 | 2 | entropy | 0.926100 | 0.002731 | 1 |

| 34 | 4 | 10 | 5 | gini | 0.925483 | 0.003617 | 4 |

| 33 | 4 | 10 | 2 | gini | 0.925483 | 0.003617 | 4 |

| 35 | 4 | 10 | 10 | gini | 0.925483 | 0.003617 | 4 |

| 26 | 4 | 1 | 10 | gini | 0.924941 | 0.003441 | 7 |

| 28 | 4 | 2 | 5 | gini | 0.924941 | 0.003441 | 7 |

| 27 | 4 | 2 | 2 | gini | 0.924941 | 0.003441 | 7 |

| 29 | 4 | 2 | 10 | gini | 0.924941 | 0.003441 | 7 |

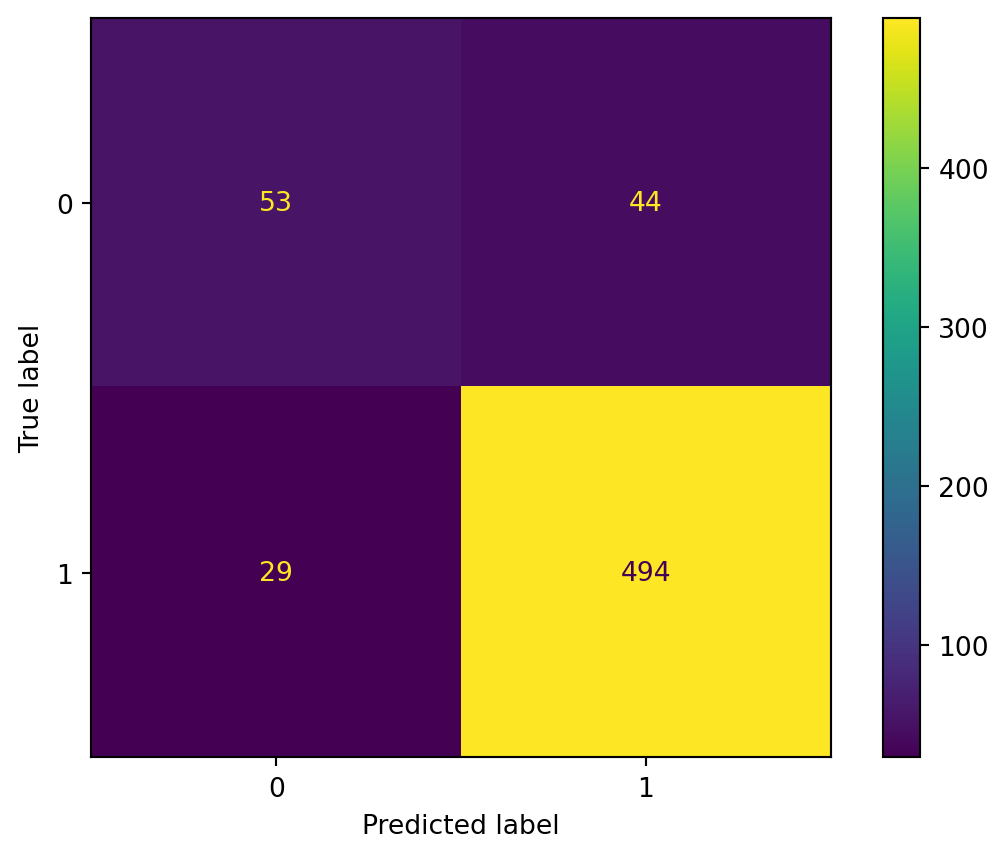

This shows us that we were not so far off from the optimal parameter when we arbitrarily chose max_depth=4. It is already a little better when we look at the confusion matrix, but we are still working with a model that overpredicts the dominant class.

If we look at the decision tree (?@fig-decision-treeCV) that this ultimately gives us, we can conclude that:

- The variables of educational attainment and income allow us to better distinguish between classes

- The unemployment rate variable is only secondary

To go further, we would need to incorporate more variables into the model. But how can we do this without risking overfitting? This will be the subject of the chapter on variable selection.

3 Conclusion

We have just briefly looked at the general approach when adopting machine learning. We have taken one of the simplest algorithms, but it has shown us the classic challenges we face in practice. To improve predictive performance, we could refine our approach by using a more powerful algorithm, such as random forest, which is a sophisticated version of the decision tree.

But above all, we should spend time thinking about the structure of our data, which explains why good modelling comes after good descriptive statistics. Without the latter, we are flying blind.

Informations additionnelles

This site was built automatically through a Github action using the Quarto

The environment used to obtain the results is reproducible via uv. The pyproject.toml file used to build this environment is available on the linogaliana/python-datascientist repository

pyproject.toml

[project]

name = "python-datascientist"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Source code for Lino Galiana's Python for data science course"

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.13,<3.14"

dependencies = [

"altair>=6.0.0",

"black==24.8.0",

"cartiflette",

"contextily==1.6.2",

"duckdb>=0.10.1",

"folium>=0.19.6",

"gdal!=3.11.1",

"geoplot==0.5.1",

"graphviz==0.20.3",

"great-tables>=0.12.0",

"gt-extras>=0.0.8",

"ipykernel>=6.29.5",

"jupyter>=1.1.1",

"jupyter-cache==1.0.0",

"kaleido==0.2.1",

"langchain-community>=0.3.27",

"loguru==0.7.3",

"markdown>=3.8",

"nbclient==0.10.0",

"nbformat==5.10.4",

"nltk>=3.9.1",

"pip>=25.1.1",

"plotly>=6.1.2",

"plotnine>=0.15",

"polars==1.8.2",

"pyarrow>=17.0.0",

"pynsee==0.1.8",

"python-dotenv==1.0.1",

"python-frontmatter>=1.1.0",

"pywaffle==1.1.1",

"requests>=2.32.3",

"scikit-image==0.24.0",

"scipy>=1.13.0",

"selenium<4.39.0",

"spacy>=3.8.4",

"webdriver-manager==4.0.2",

"wordcloud==1.9.3",

]

[tool.uv.sources]

cartiflette = { git = "https://github.com/inseefrlab/cartiflette" }

gdal = [

{ index = "gdal-wheels", marker = "sys_platform == 'linux'" },

{ index = "geospatial_wheels", marker = "sys_platform == 'win32'" },

]

[[tool.uv.index]]

name = "geospatial_wheels"

url = "https://nathanjmcdougall.github.io/geospatial-wheels-index/"

explicit = true

[[tool.uv.index]]

name = "gdal-wheels"

url = "https://gitlab.com/api/v4/projects/61637378/packages/pypi/simple"

explicit = true

[dependency-groups]

dev = [

"nb-clean>=4.0.1",

]

To use exactly the same environment (version of Python and packages), please refer to the documentation for uv.

| SHA | Date | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| dfae2749 | 2025-12-25 15:18:33 | lgaliana | Details in new classification chapter |

| 8c2b986d | 2025-12-25 11:31:10 | lgaliana | Forgot to change chapter name |

| 9a1f85b6 | 2025-12-25 12:29:25 | Lino Galiana | Decision tree rather than SVM (#668) |

| 3e04ed3c | 2025-11-24 20:08:05 | lgaliana | Avoid deprecated ravel method and fix notebooks launch url |

| 94648290 | 2025-07-22 18:57:48 | Lino Galiana | Fix boxes now that it is better supported by jupyter (#628) |

| 91431fa2 | 2025-06-09 17:08:00 | Lino Galiana | Improve homepage hero banner (#612) |

| 48dccf14 | 2025-01-14 21:45:34 | lgaliana | Fix bug in modeling section |

| 8c8ca4c0 | 2024-12-20 10:45:00 | lgaliana | Traduction du chapitre clustering |

| a5ecaedc | 2024-12-20 09:36:42 | Lino Galiana | Traduction du chapitre modélisation (#582) |

| ff0820bc | 2024-11-27 15:10:39 | lgaliana | Mise en forme chapitre régression |

| bb943aab | 2024-11-26 15:18:41 | Lino Galiana | hope works (#579) |

| e7fd1ff3 | 2024-11-25 18:20:32 | lgaliana | rename classification chapter |

Citation

@book{galiana2025,

author = {Galiana, Lino},

title = {Python Pour La Data Science},

date = {2025},

url = {https://pythonds.linogaliana.fr/},

doi = {10.5281/zenodo.8229676},

langid = {en}

}